Click through amazing historical photos dating back to the 1800s and learn more about the beginning of New Orleans' paddling community.

Swipe to see amazing historical photos dating back to the 1800s and learn more about the beginning of New Orleans' paddling community.

Click through amazing historical photos dating back to the 1800s and learn more about the beginning of New Orleans' paddling community.

Swipe to see amazing historical photos dating back to the 1800s and learn more about the beginning of New Orleans' paddling community.

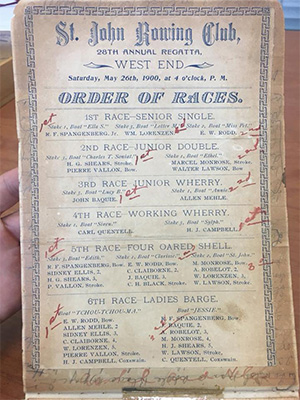

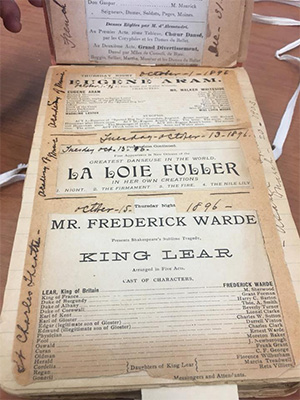

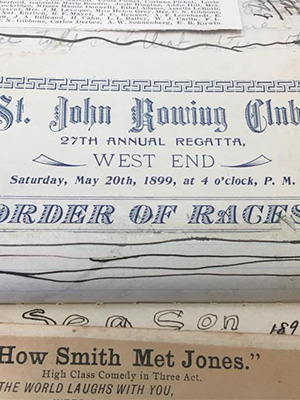

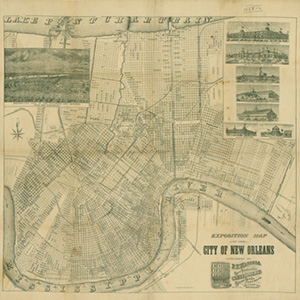

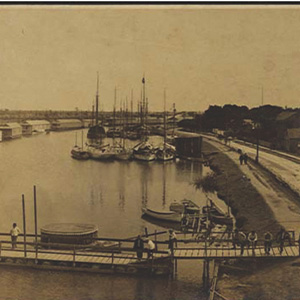

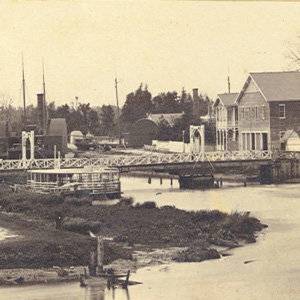

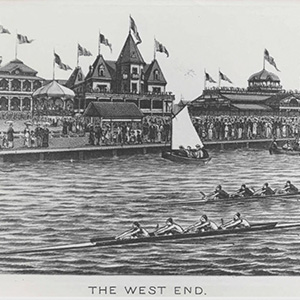

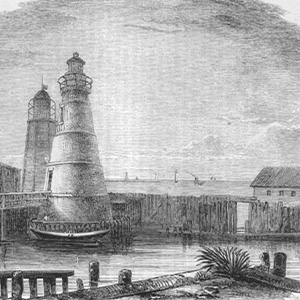

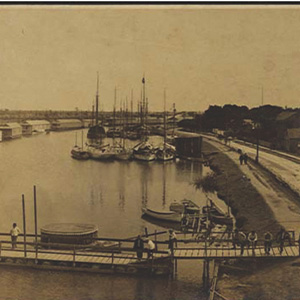

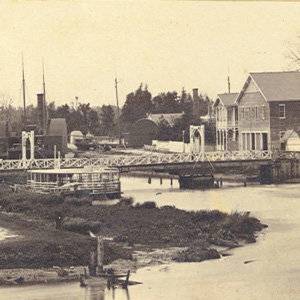

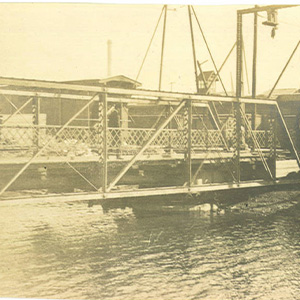

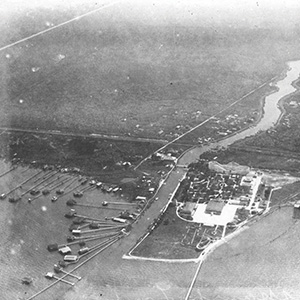

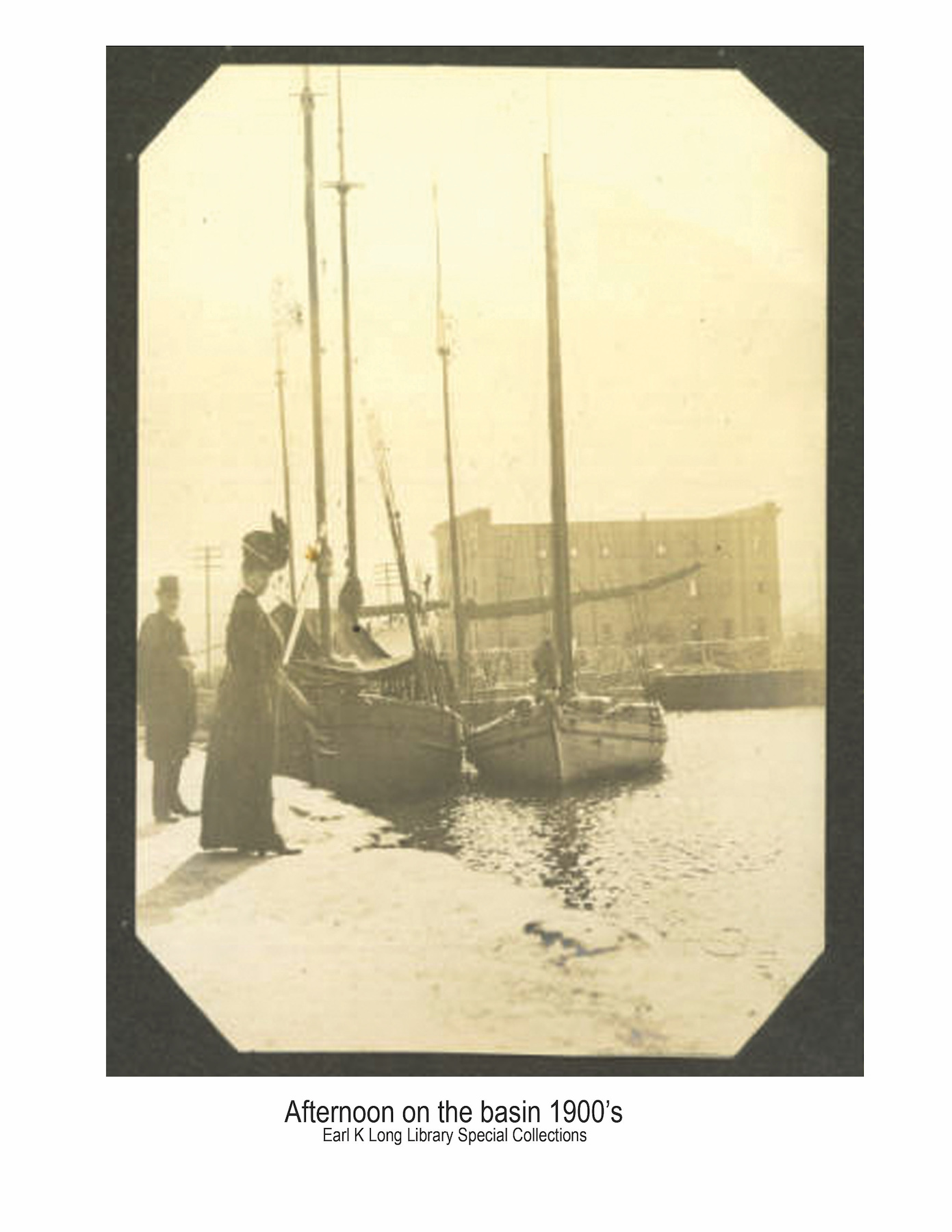

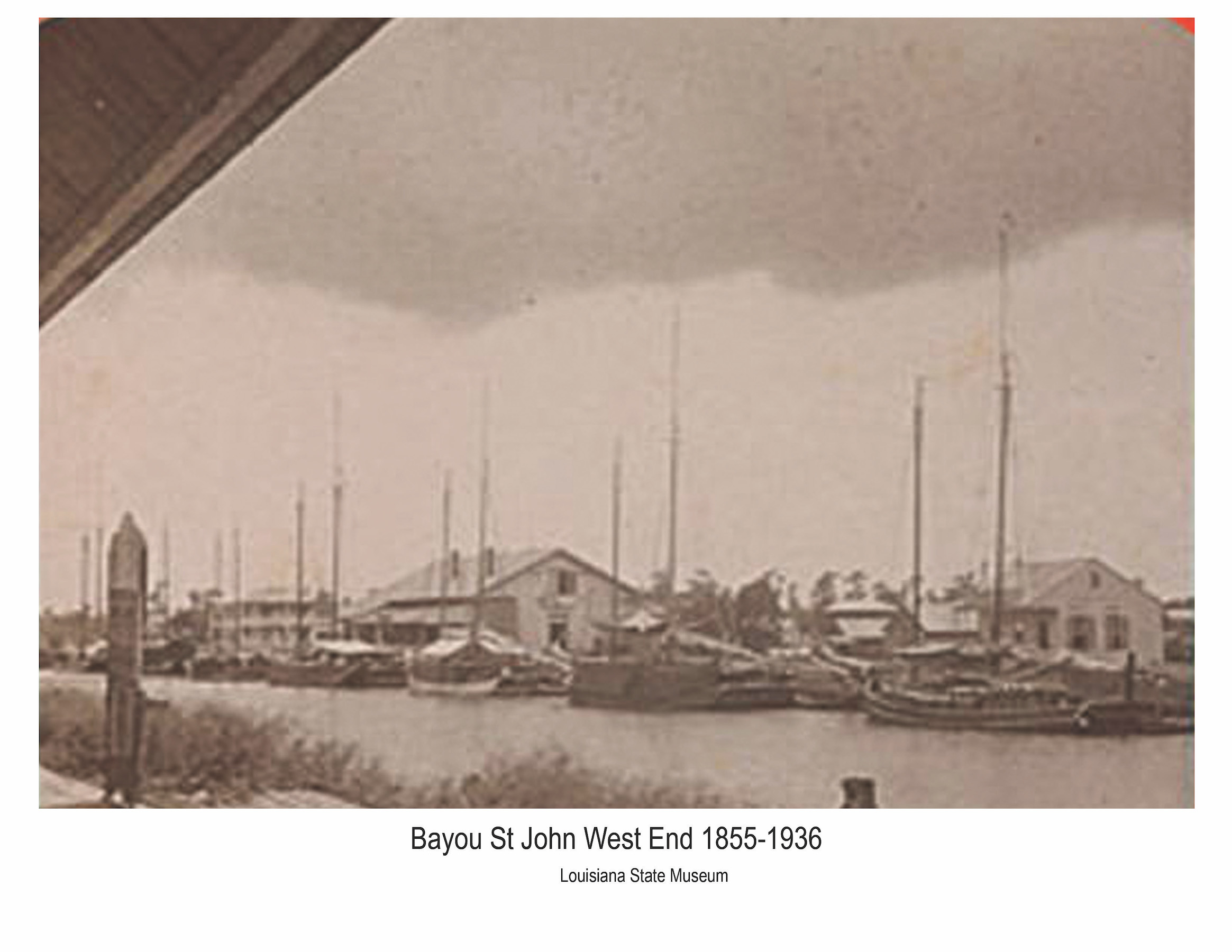

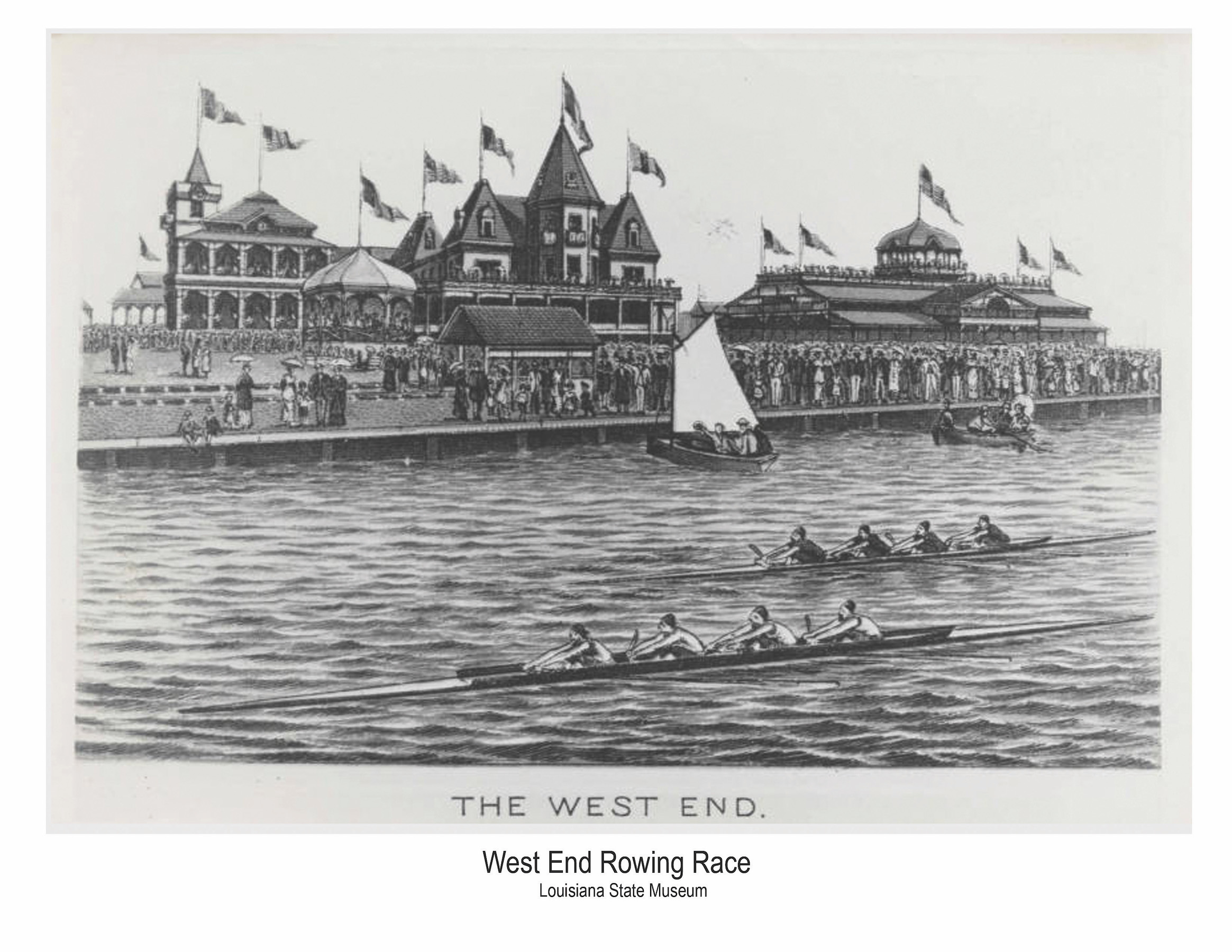

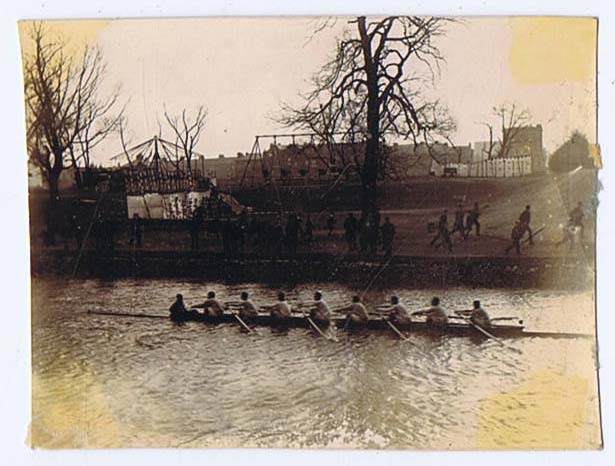

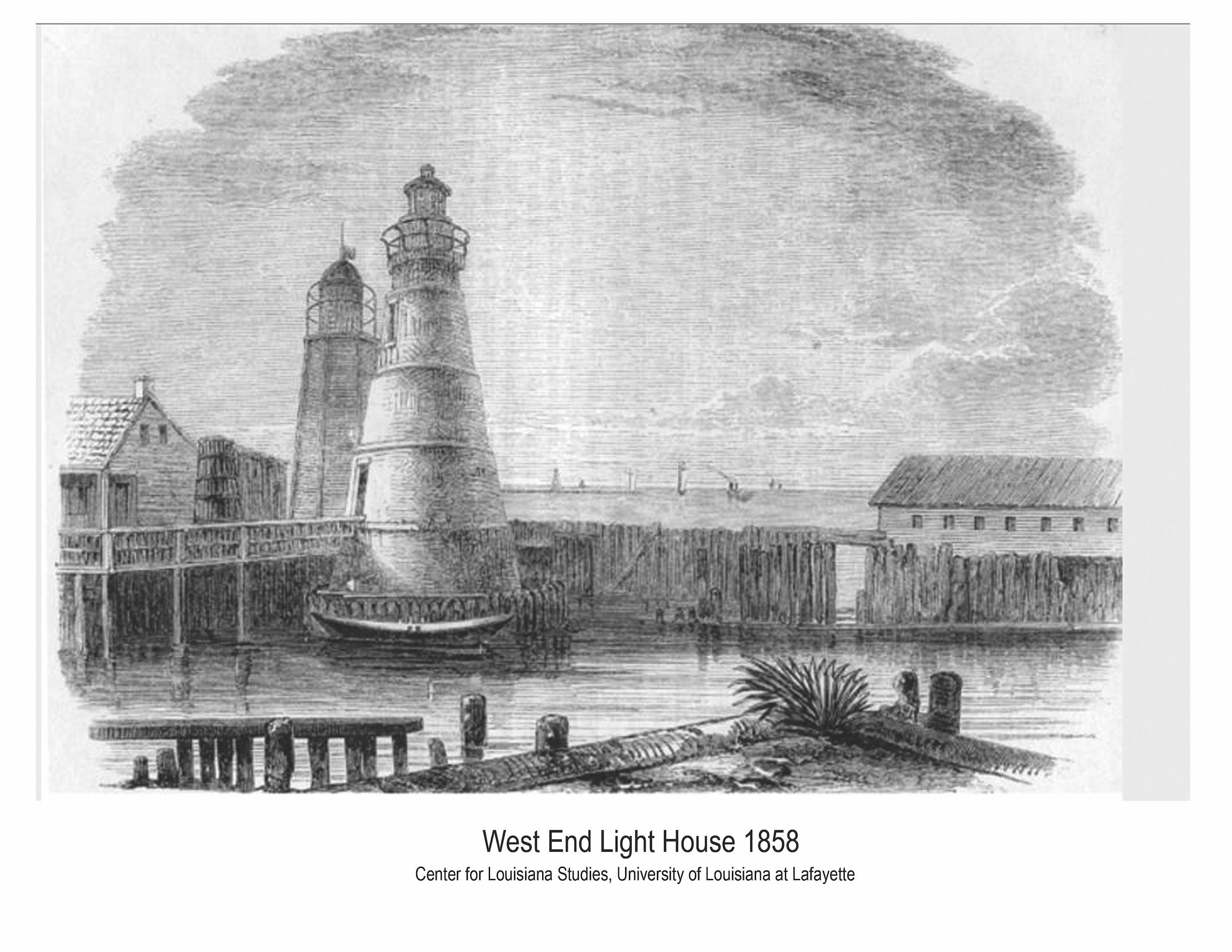

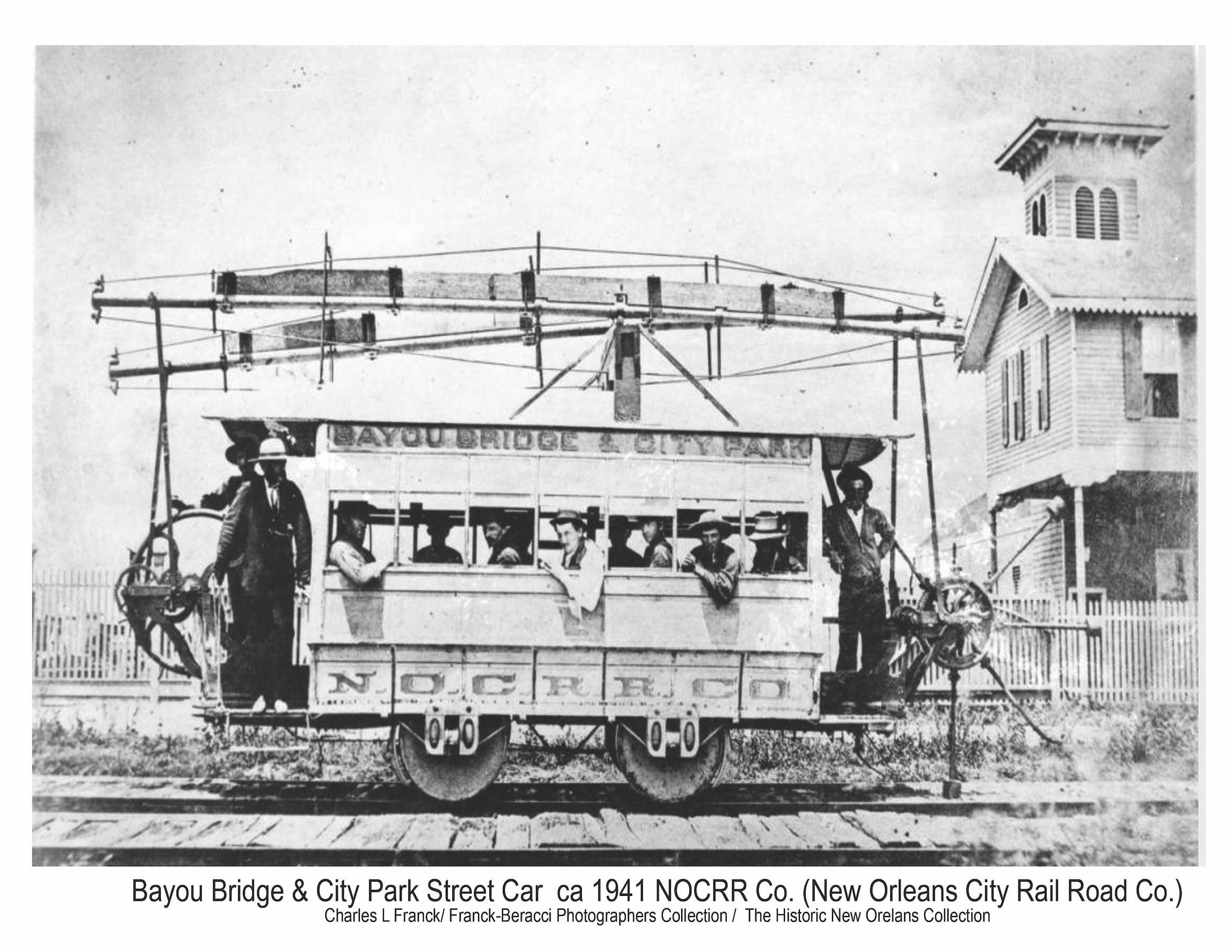

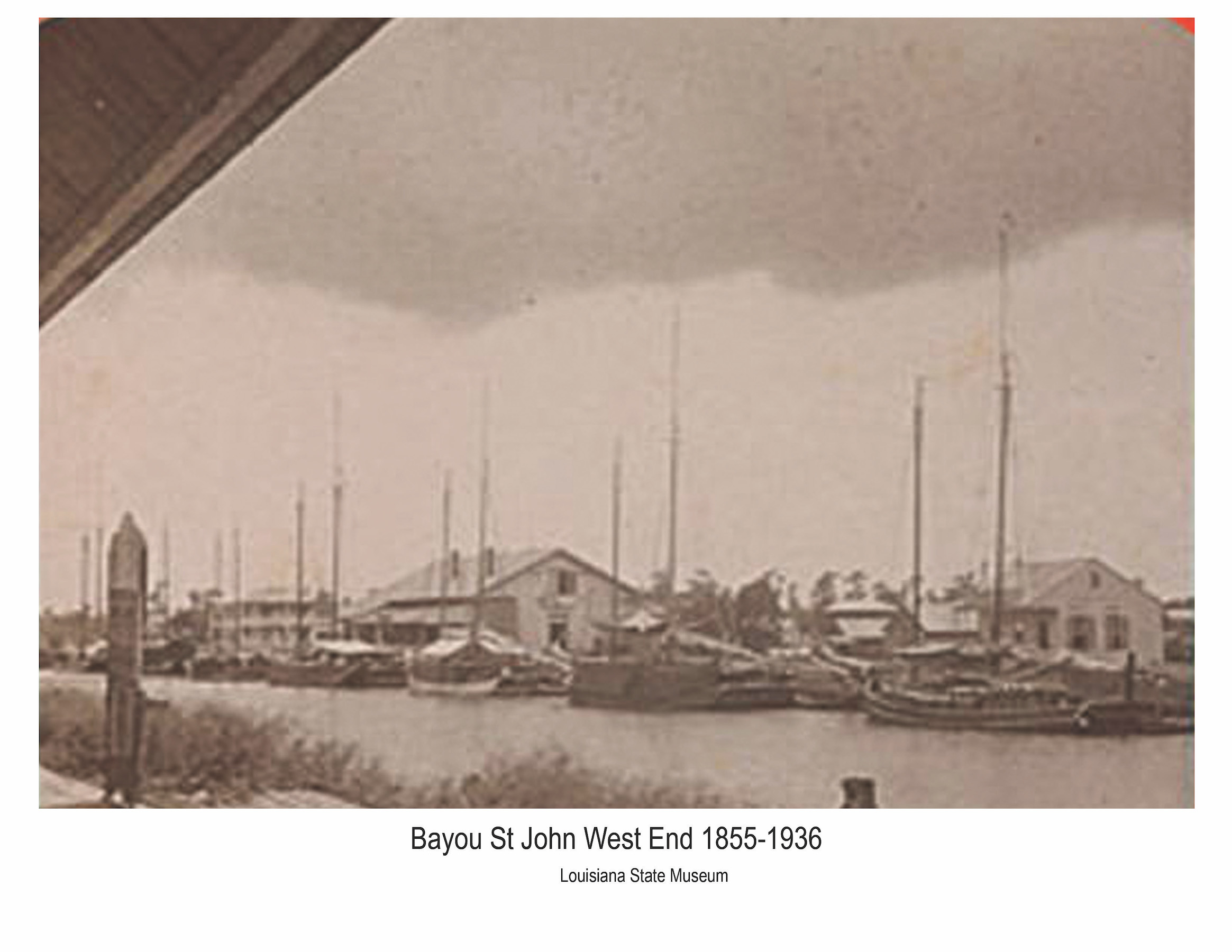

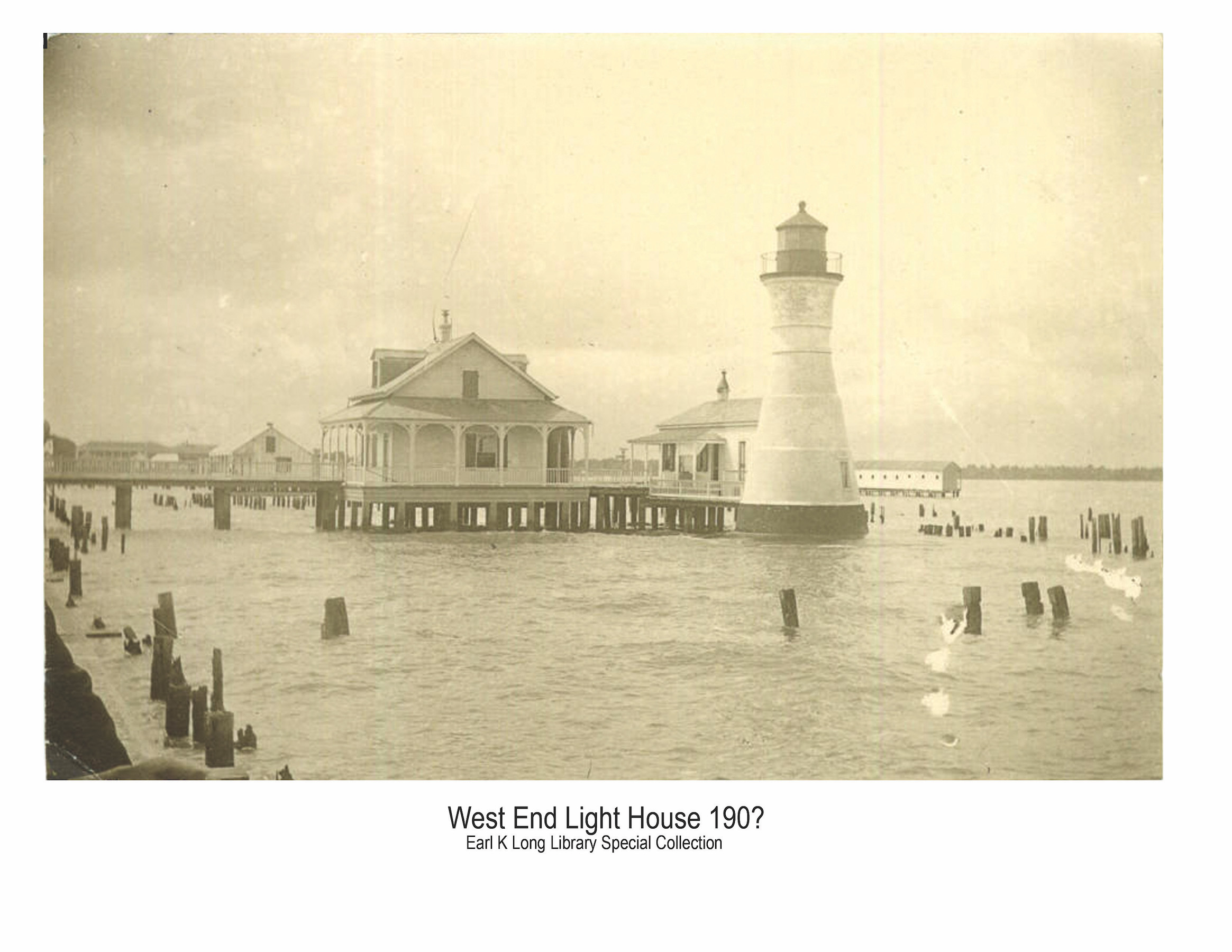

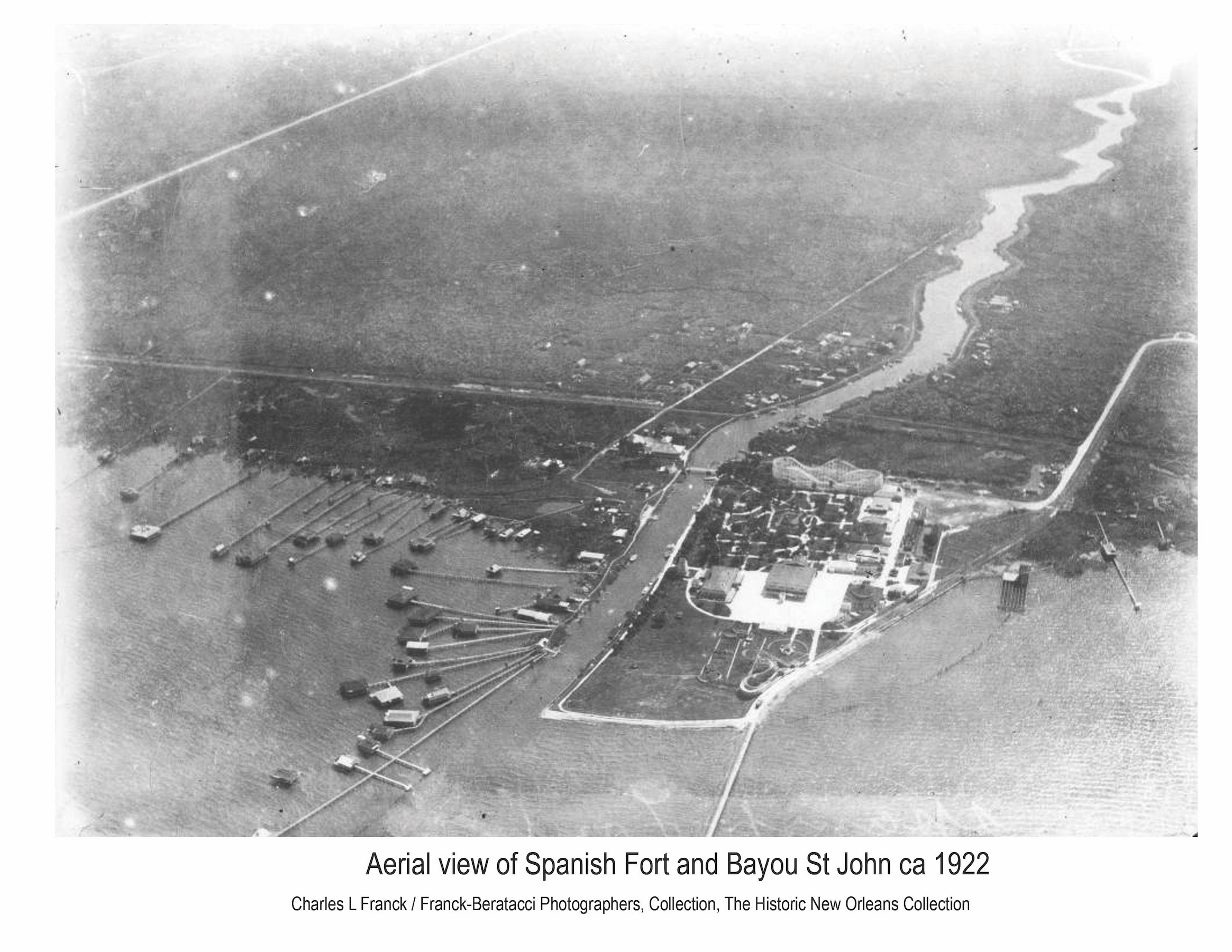

Irish immigrants dug the New Basin Canal between 1832 and 1835, and, a few years later in 1838, restaurants and hotels popped up where the canal met the lake, otherwise known as The West End. By 1840, passengers could enjoy a leisurely, awning-covered, one-hour barge service down the New Basin Canal for only 20 cents. Once the New Orleans and Carrollton Railway laid its final track in 1853, passengers could take the 35-minute train trip, covering 10 miles for just 25 cents. Watching and betting on rowing races grew so popular in the late 19th century that the St. John Rowing Club had to build a clubhouse and grandstand to allow for better viewing and to encourage bigger betting on the four mile races (Stuart).

Irish immigrants dug the New Basin Canal between 1832 and 1835, and, a few years later in 1838, restaurants and hotels popped up where the canal met the lake, otherwise known as The West End. By 1840, passengers could enjoy a leisurely, awning-covered, one-hour barge service down the New Basin Canal for only 20 cents. Once the New Orleans and Carrollton Railway laid its final track in 1853, passengers could take the 35-minute train trip, covering 10 miles for just 25 cents. Hotels lured visitors to their shores (including a boardwalk and bandstand) with promises of swimming, fishing, and entertaining spectator sports, like rowing. This attention is why and how many rowing clubs were formed in New Orleans. Watching and betting on rowing races grew so popular in the late 19th century that the St. John Rowing Club had to build a clubhouse and grandstand to allow for better viewing and to encourage bigger betting on the four mile races (Stuart).

Even though rowing was popular in the East after the Revolutionary War, it did not reach the West and the South until after 1800. Rowing was less expensive than yachting and it offered men the chance to show athletic prowess in direct elements. By the late 1830’s, New Orleans had caught wind of the sport. Rowing appealed especially to the middle-class youth, who, according to The Rise of Sports in New Orleans, “lacked the money and leisure to command expensive sailing boats but who could band together to purchase rowing equipment.” And then, in 1837, a Daily Picayune editor dared the young men of the city to form rowing clubs and use their time more productively (Somers 42).

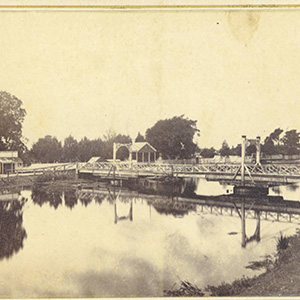

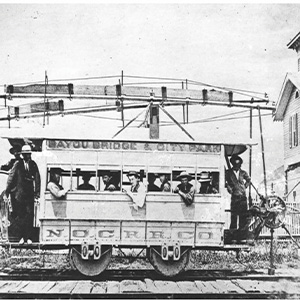

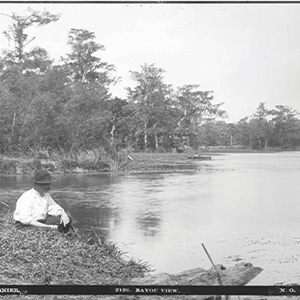

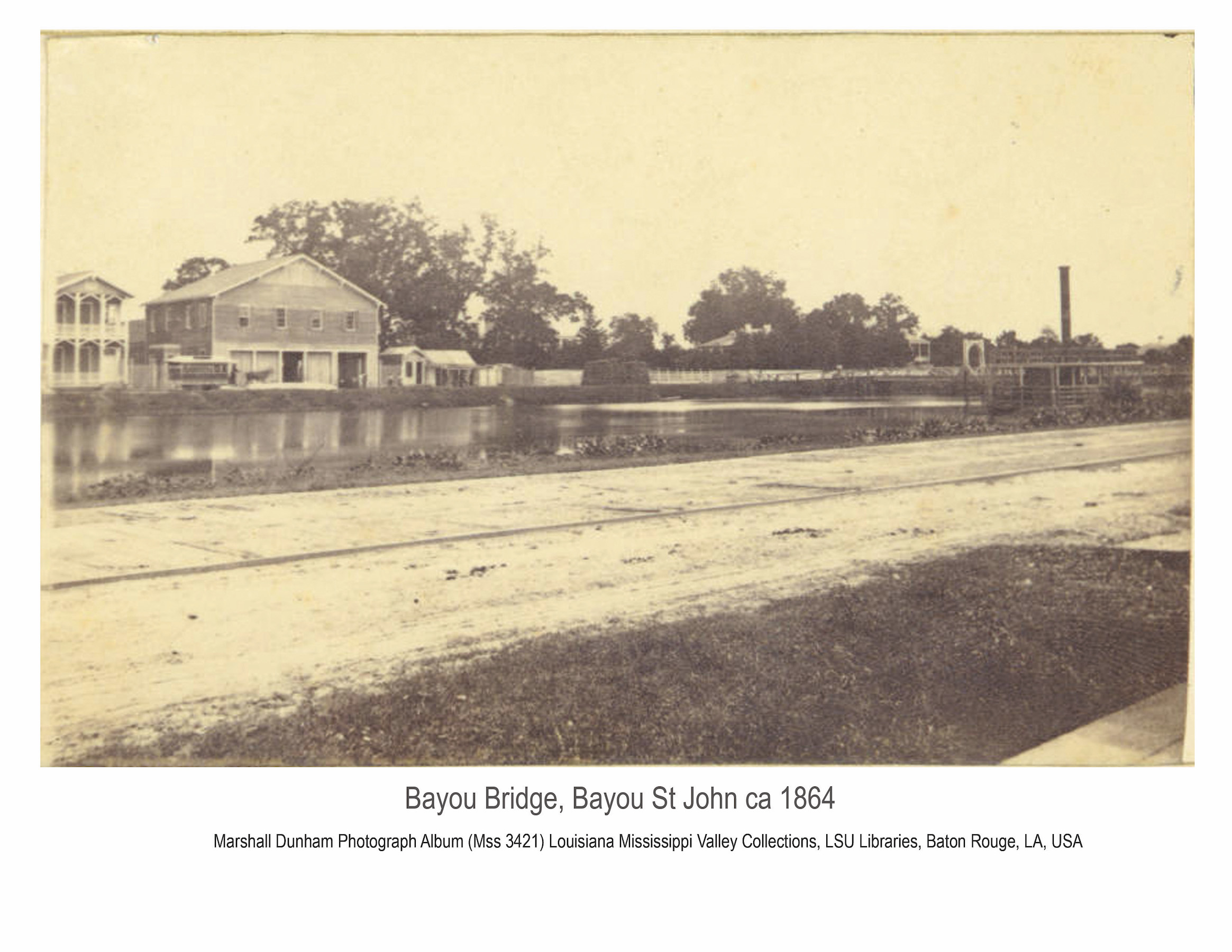

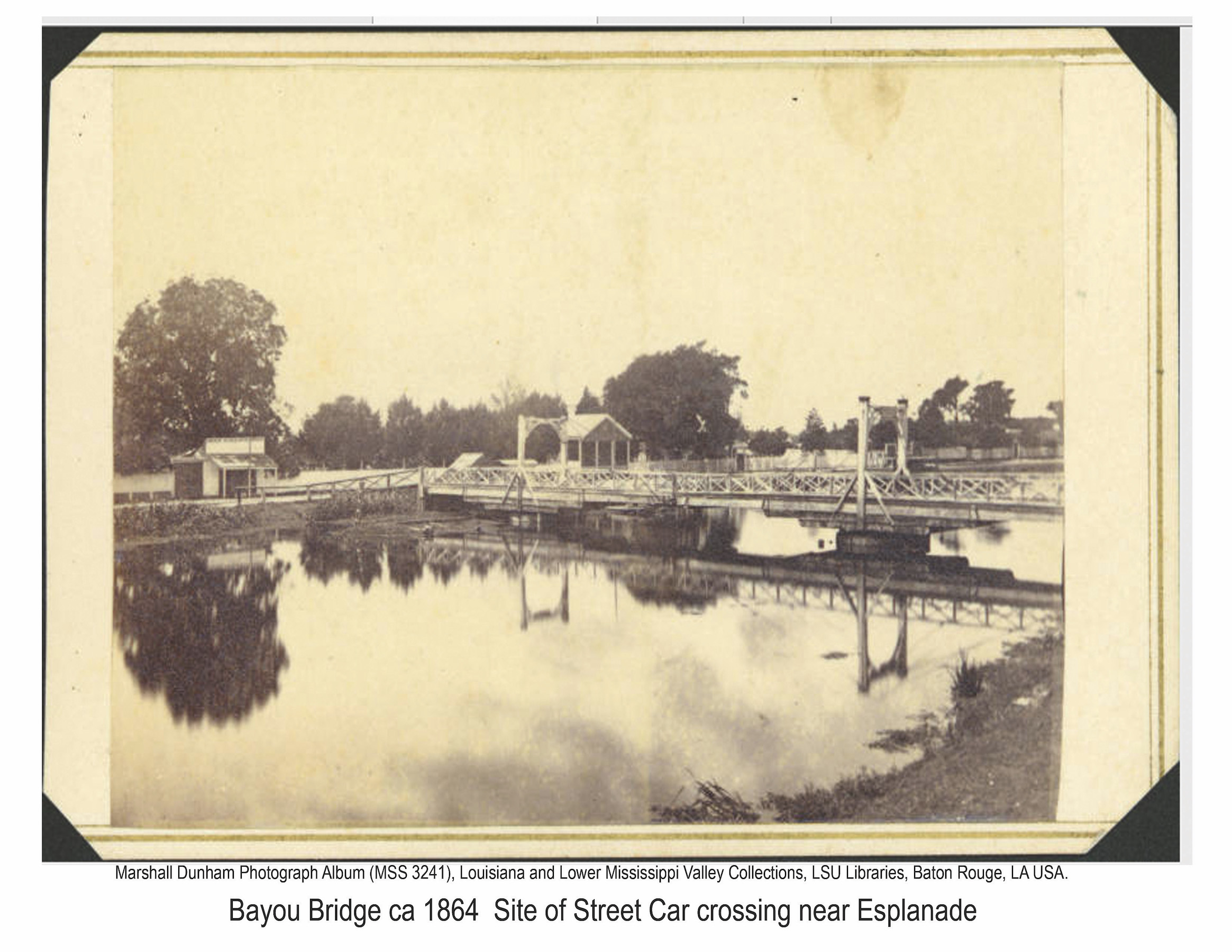

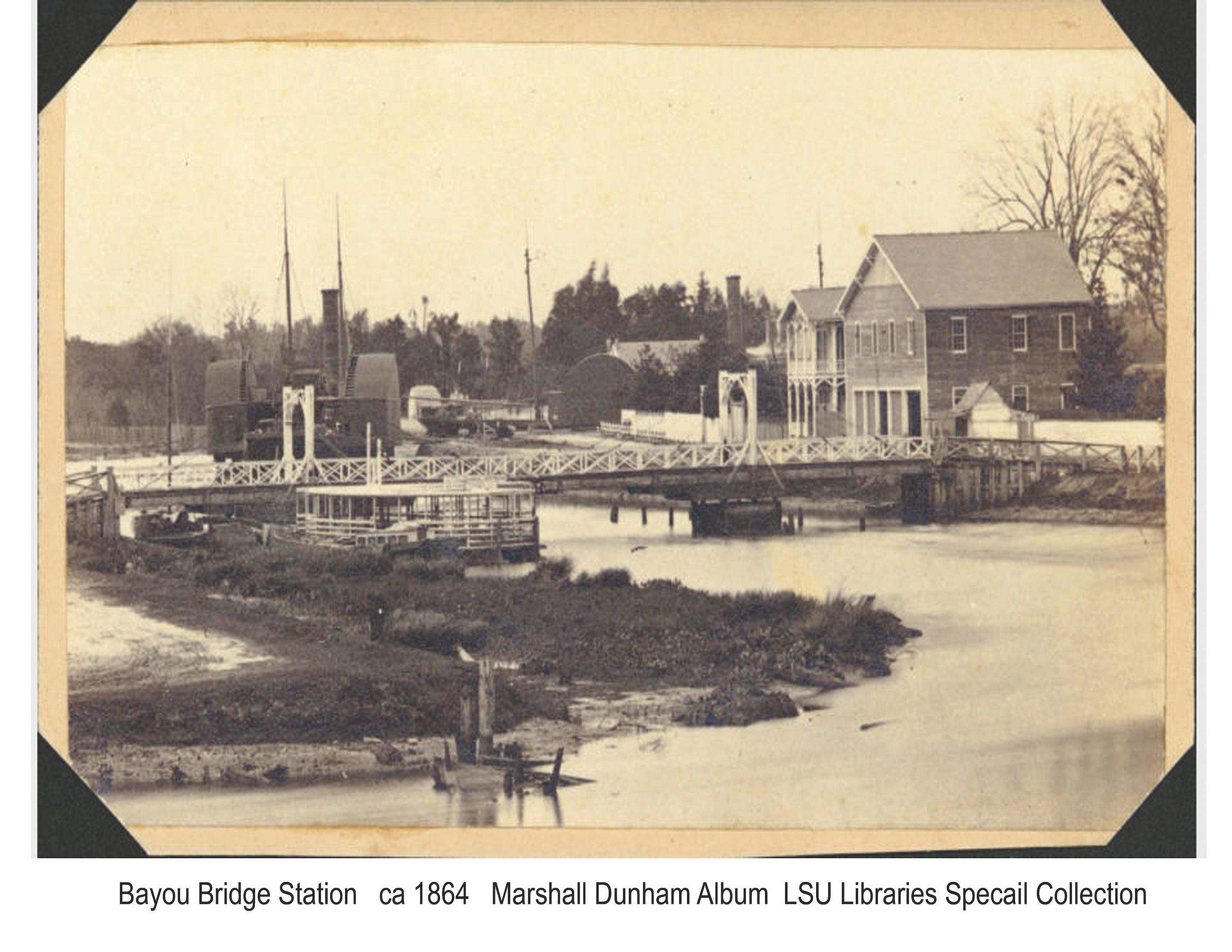

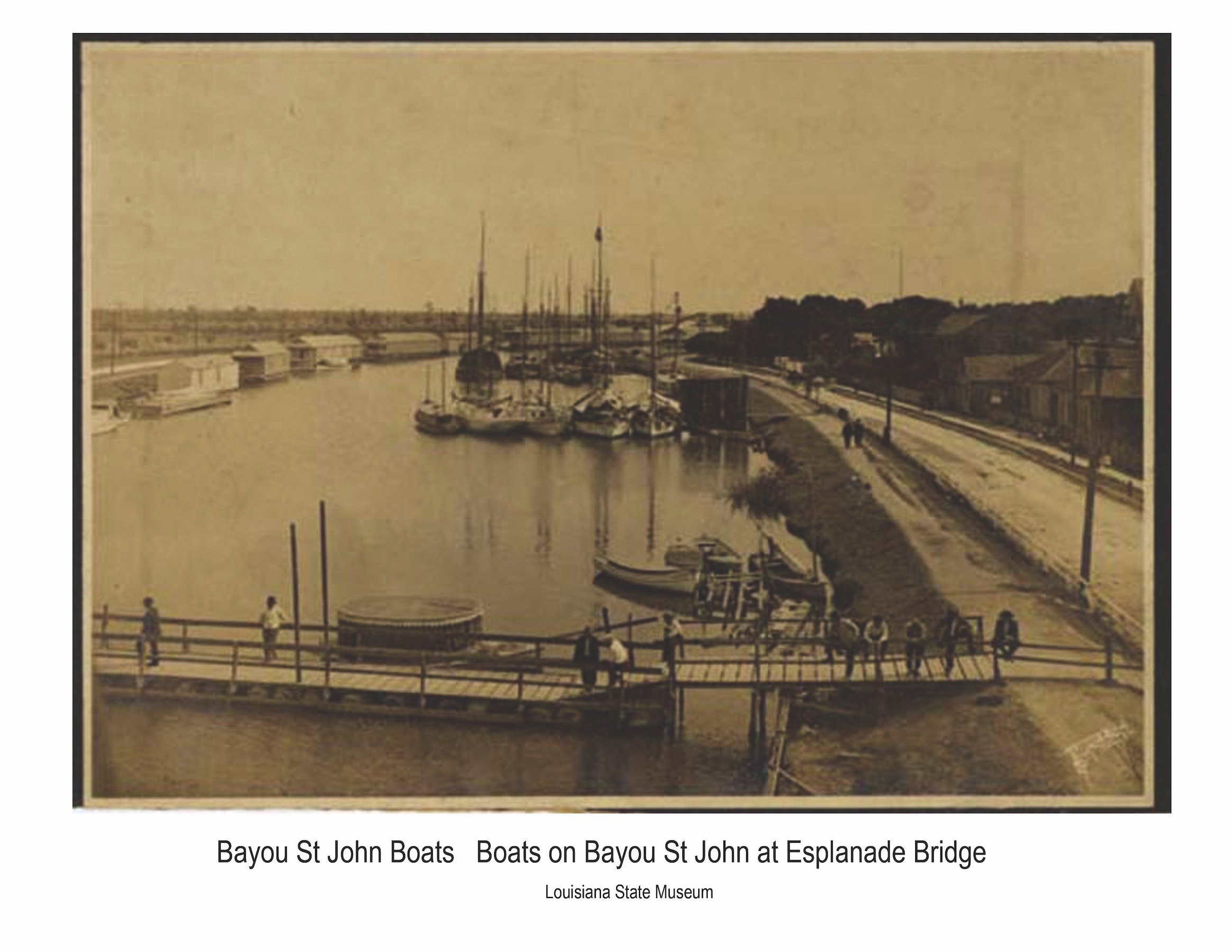

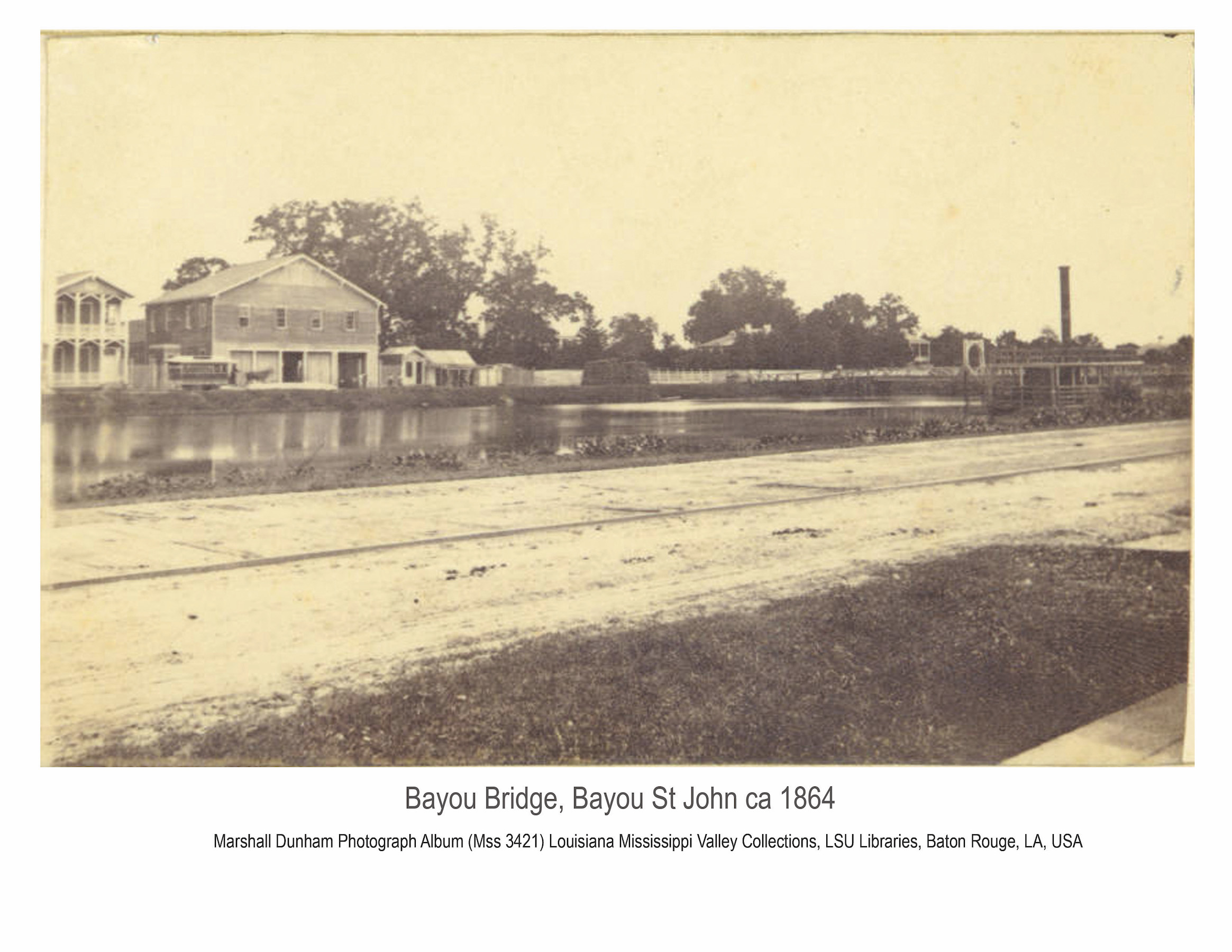

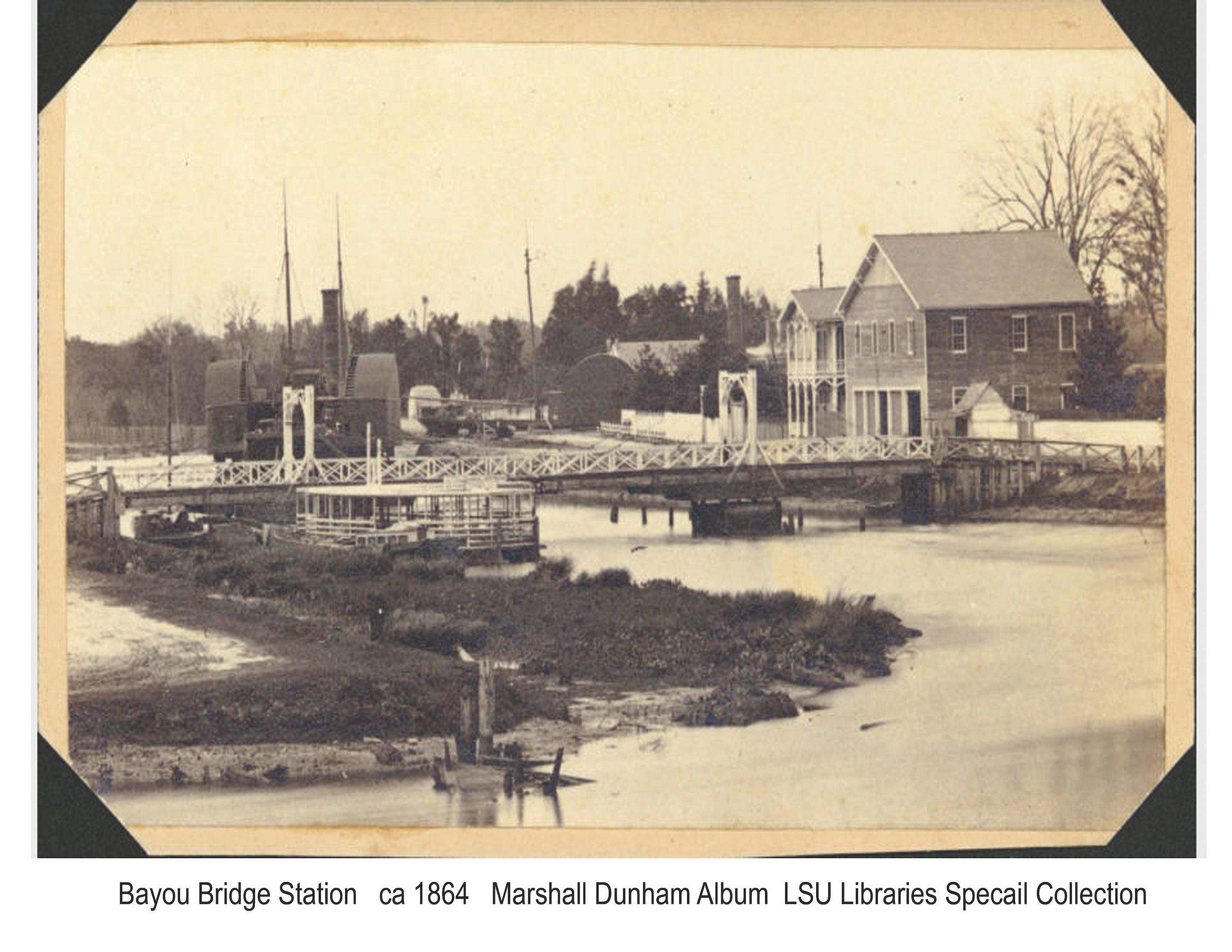

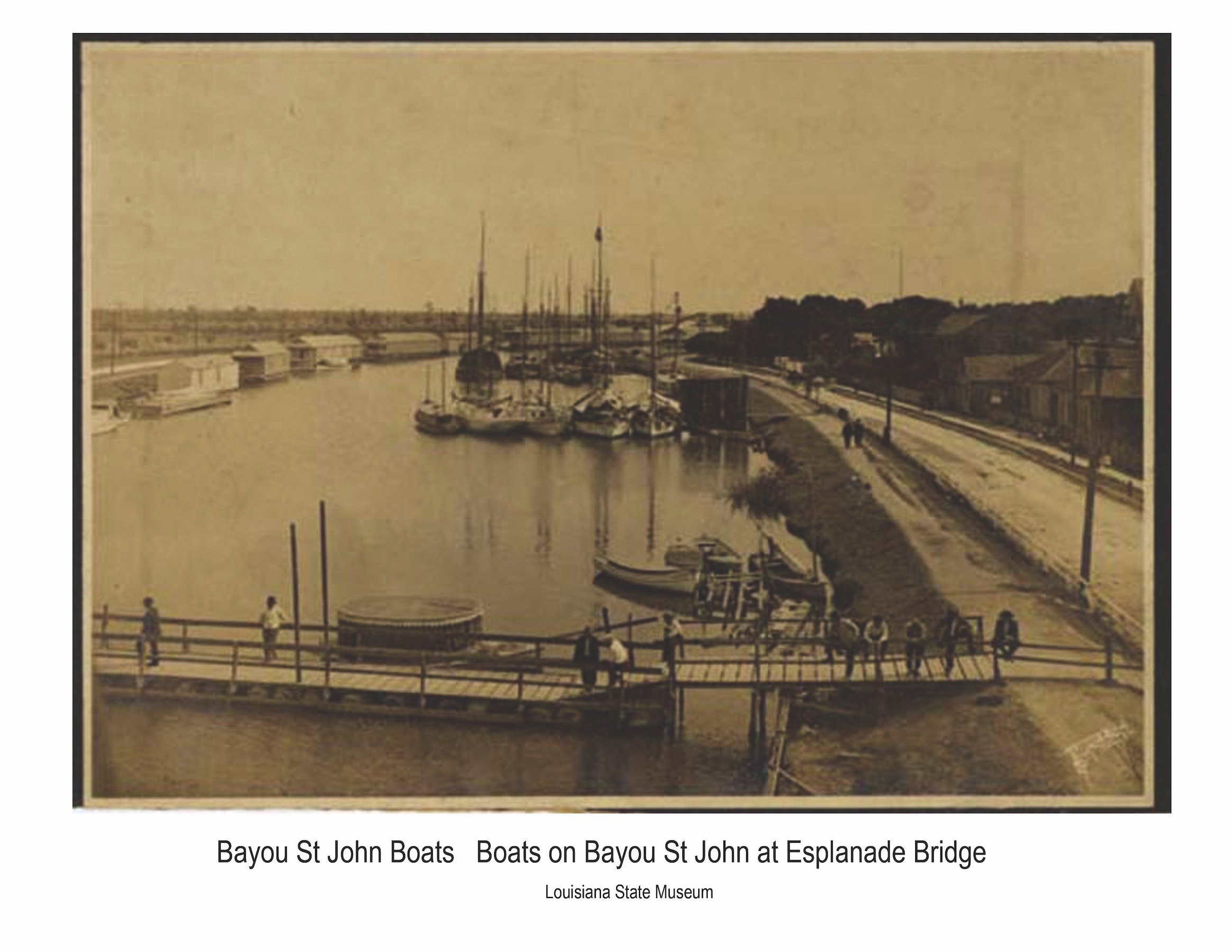

On July 21, 1837, The New Orleans Daily Picayune suggested that a rowing club might benefit the young men of the city. Faster than expected, especially by current New Orleans time standards, young men responded to the challenge; on August 9, 1837, the New Orleans Daily Picayune praised the men’s efforts and their desire to engage in something other than “lazy inactivity, quarrelling, billiard playing, drinking and dueling.” They formed a structured rowing club composed of strong, intelligent men and planned to have boats skimming the surface in no time. In fact, they had immediate plans to build a boathouse at Bayou Bridge for $1000 even though they had yet to decide on a name (Somers 42).

This first rowing club’s exuberance inspired many others, and at least eight more clubs were formed after 1837: Lady of Lyons, Wave, Ariel, Algerine, Knickerbocker, Edwin Forrest, Washington, and Locofo. As soon as clubs formed, the regattas began. On January 8, 1839, the New Orleans Daily Picayune reported that the New Orleans’ Ariel Club and two clubs from Mobile, AL would face each other in New Orleans’ “first regular regatta.” Even though this race ended poorly for the city’s rowers, they kept trying. New Orleans teams would face Mobile teams again in April for a $1000 prize (Somers 42, 47).

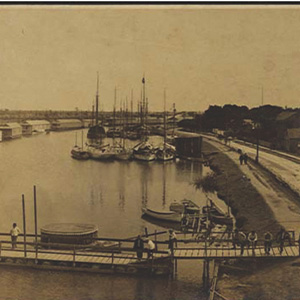

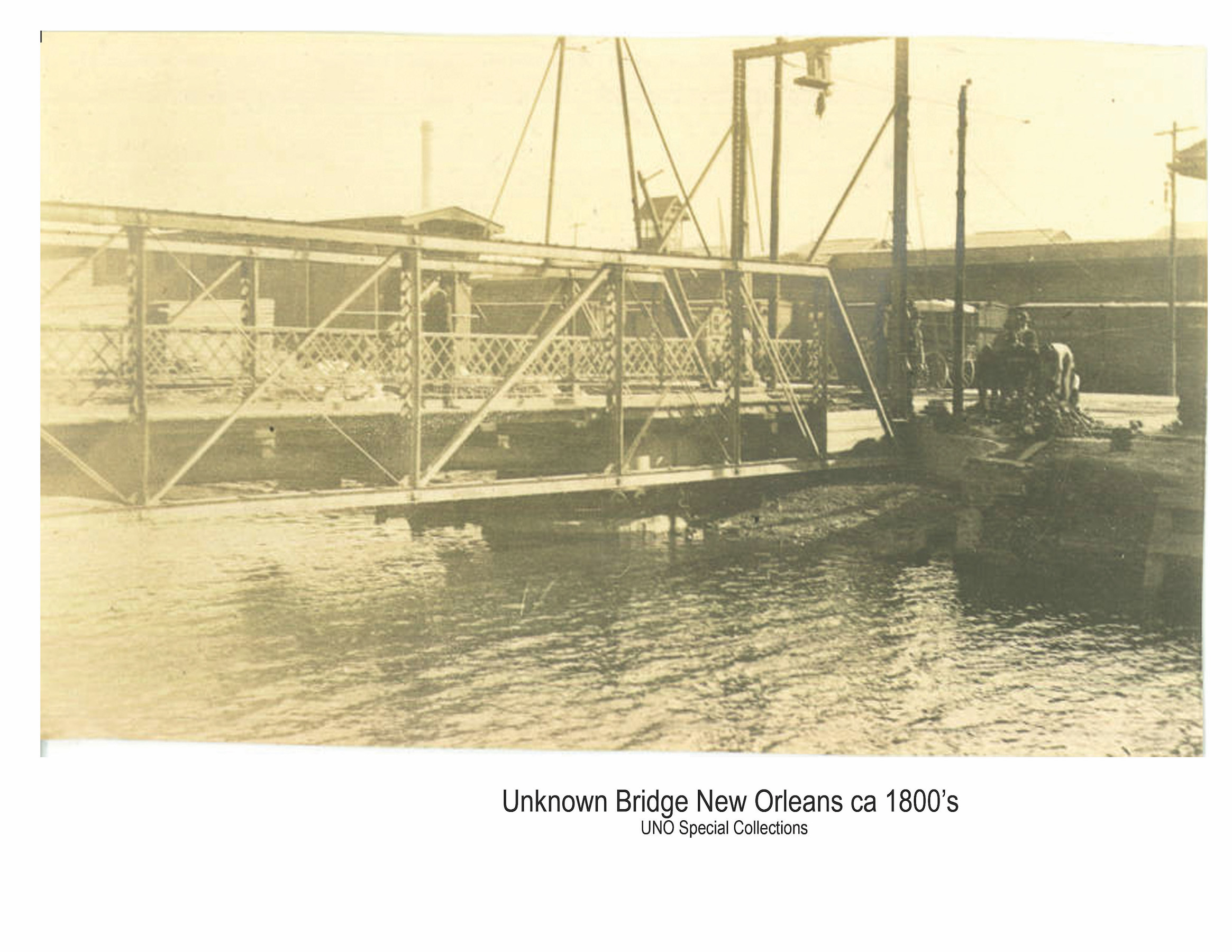

At first, most clubs built their boathouses along the New Basin Canal, but, later, most clubs kept their boats on the Mississippi. A regionally famous boat builder in Algiers, John Mahoney, supplied most of the rowers with their boats and other necessary equipment. It seemed New Orleans was on the trajectory to become a rowing town. Unfortunately, a devastating flood in 1844 demolished almost all the boathouses and boats, causing a fifteen year rowing drought (Somers 47).

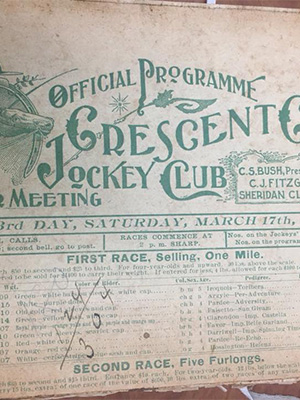

In 1859, after fifteen years of inactivity in the rowing community, a group of athletic men decided to reignite the sport by forming the Monoma Boat Club. They held a string of races amongst themselves on Lake Pontchartrain, and, soon after, another rival club, Pioneer, formed. In the summer in 1860, the Monoma and the Pioneer Boat Clubs decided to race for a nice oar set and the winning club’s colors. The rivalry was tense, and the Crescent stoked the fire by encouraging residents to watch the race and informing them that rowing was “‘an aquatic sport, bringing out muscle and science, quite as exciting as cricket and baseball.

Because yachting was considered a rich man’s sport, many American’s favored rowing as their aquatic sport of choice. A rowing resurrection occurred after the Civil War ended in 1865, and, by the 1870’s, the United States had over 200 clubs. Most clubs were governed by the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen (now known as US Rowing), founded by Philadelphia’s Schuylkill Navy in 1873. The NAAO’s purpose was to sponsor annual national championship regattas and to keep rowing an amateur sport by restricting professionals in all forms. With a governing body and a plethora of clubs to compete, it’s no wonder that, for a generation after the Civil War, rowing became one of America’s most popular sports to participate in (Somers 151).

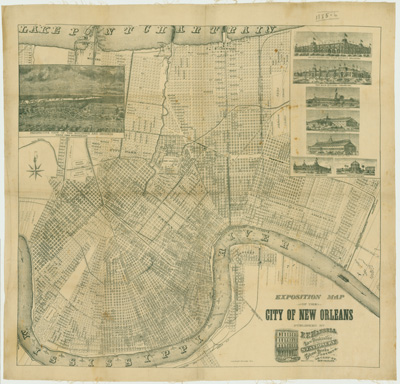

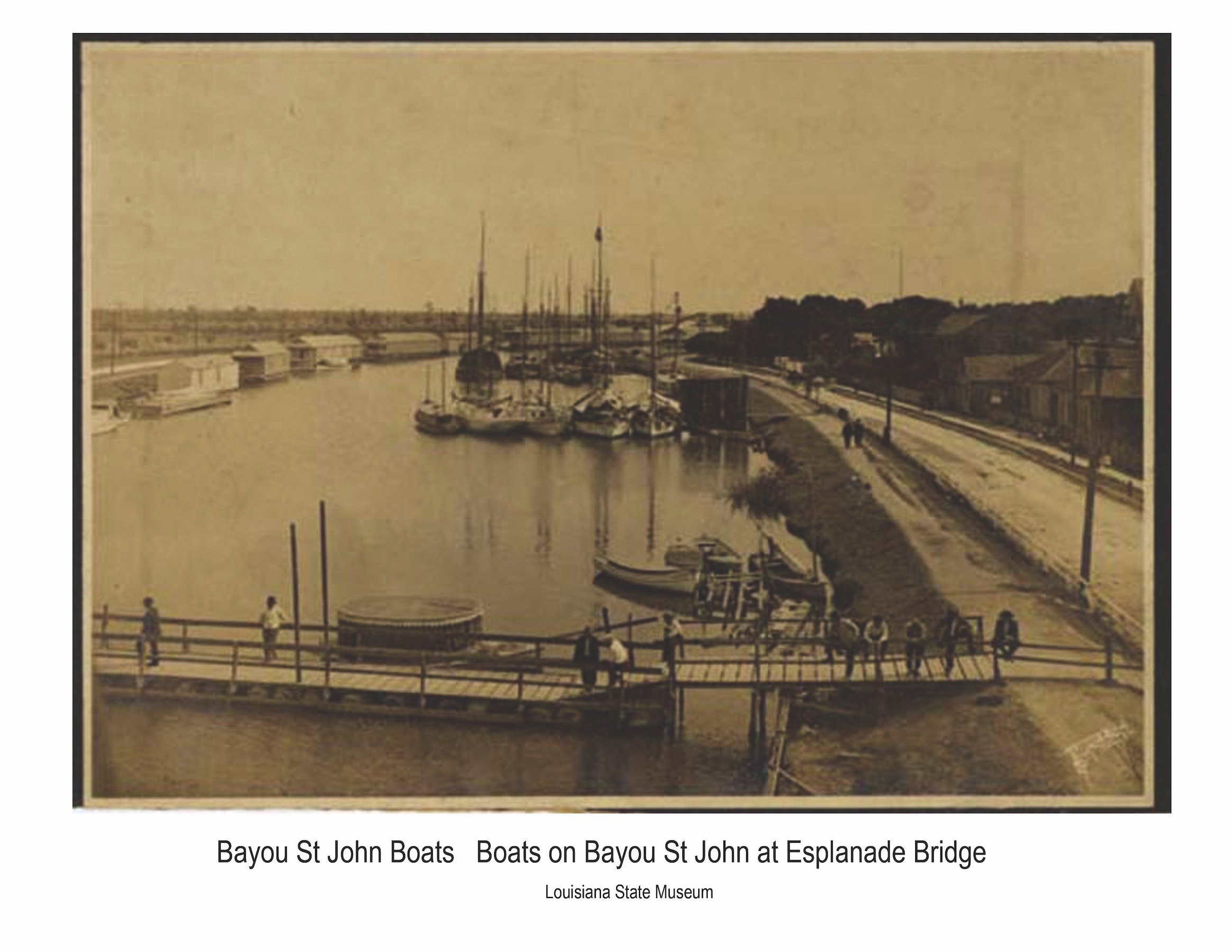

In the middle of 1872, seven years after the Civil War’s final battle, the rowing resurrection arrived in New Orleans. The New Orleans Daily Picayune reported, on May 14, 1872,that the city’s “first and best young men” founded both the St. John Rowing Club and the Pelican Rowing Club. With boathouses on Bayou St. John and race schedules posted, word spread. By 1874, New Orleans was home to more than a dozen clubs, and by 1900, there were at least thirty clubs in town. The growing number of clubs called for more governing bodies, and so more rowing associations formed accordingly. Boats were soon all over the city, with boat docks and clubhouses on Bayou St. John, Lake Pontchartrain, and the New Basin Canal. Some clubs were even braving the Mississippi (Somers 151-152).

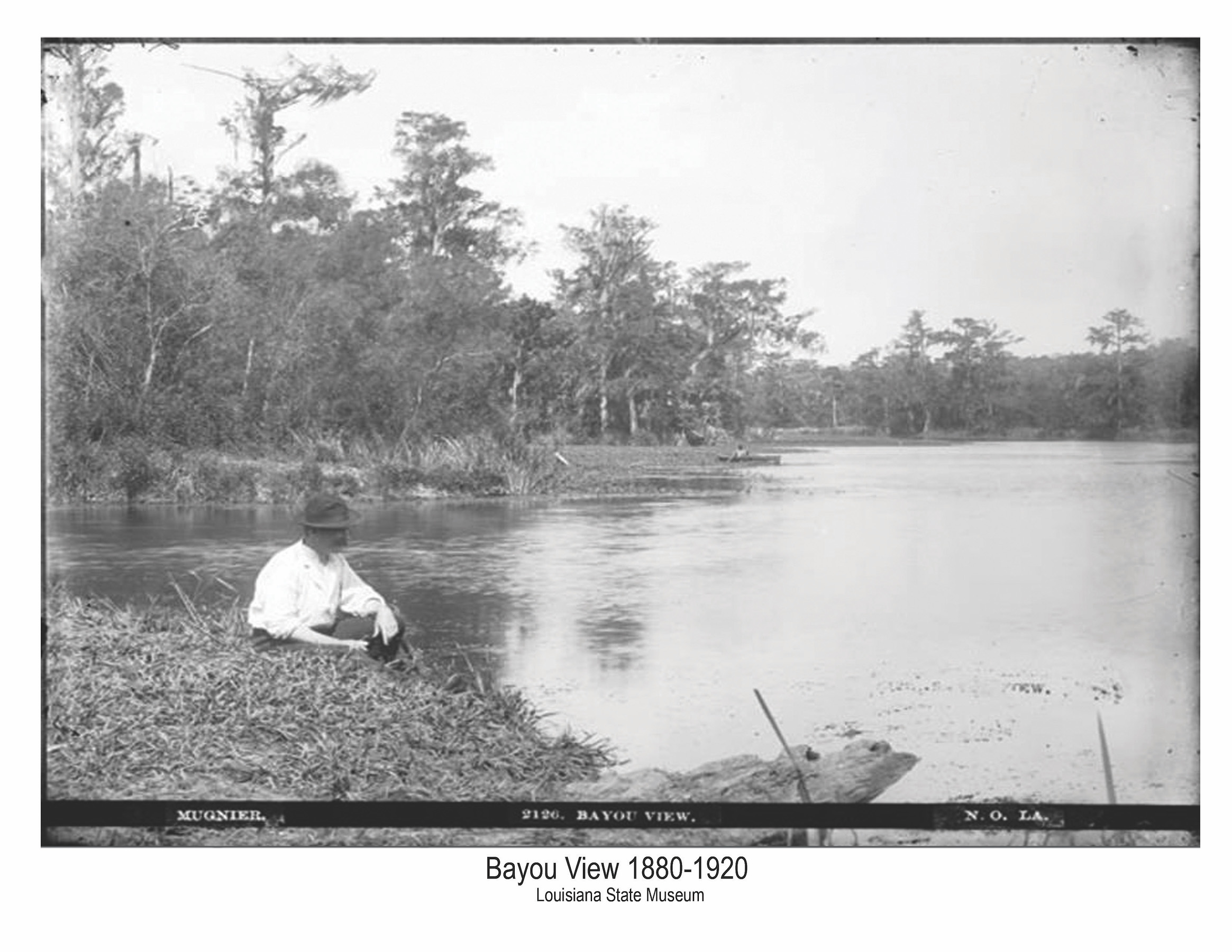

On September 5, 1872, The Times Picayune excitedly reported that Bayou St. John would no longer be the “sewerage drain of the city.” The waters were purifying slowly but surely, and the city hoped that Bayou St. John would return to the clear, pure stream of its former life. Due to this reclamation, more rowing clubs were formed and more people were exposed to rowing. In fact, crowds of at least five hundred people packed the bayou to watch the St. John Rowing Club beat Odalisque.

In 1872, the Times Picayune reported huge crowds on the banks of Bayou St. John for the inter-club championship between the two best teams of St. John Rowing Club in the article, “The St. John Rowing Club.” Esplanade and Bayou Bridge were packed and the crowd spread the length of the race. The St. John and Pelican clubhouses burst capacity. This was a duel to witness. The deal: “from the island to the boat-house, distance a mile and a half, for the championship.” There wasn’t much else to decide, since both boats were of the same design by John Mahoney, and so there was no advantage to either. The Emma team won the race, but the Abby team claimed foul and were declared winner. A re-match was in order.

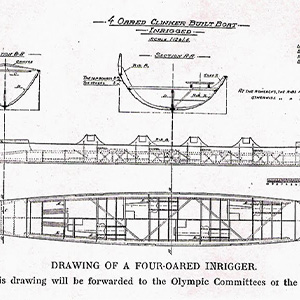

John Mahoney, one of the leading shipbuilders of the 1800’s, practiced his craft at One Patterson Street, alongside the plantations and dry docks of the Algiers community. Octave J. Bocage, a free man of African and Acadian descent, was his most promising employee. In a revolutionary moment for a man of color in 1872, Bocage opened his own shipbuilding business, Octave J. Bocage & Sons. Octave and his sons professionally designed and built barges, oyster boats, high-speed power boats, and even steamboats. Bocage and his sons were world class and award-winning builders, respected by whites, African Americans, and Creoles alike (“Algiers”).

John Mahoney, one of the leading shipbuilders of the 1800’s, practiced his craft at One Patterson Street, alongside the plantations and dry docks of the Algiers community. A well-respected man, Mahoney hired young men of African descent to work at Mahoney’s Shipyard. Octave J. Bocage, a free man of African and Acadian descent, was his most promising employee. In a revolutionary moment for a man of color in 1872, Bocage opened his own shipbuilding business, Octave J. Bocage & Sons. Octave and his sons professionally designed and built barges, oyster boats, high-speed power boats, and even steamboats. They built for individuals and companies, such as The Tropical Trading Company of Central America and Louisiana Oyster’s Commission. They were even recognized for their “skill, craftsmanship and artistry” at the 1889 Paris World’s Exposition, where they exhibited five boats. The boat commissioned by the International Life Saving Boat Company took home an award, world-wide success, and 20,000 francs ($3,846.75 USD). Bocage and his sons were world class and award-winning builders, respected by whites, African Americans, and Creoles alike (“Algiers”).

Before the war, rowing was reserved for members of high society, and this trend continued only for a short time after the war. On August 25, 1872, New Orleans Daily Picayune boasted that the Pelican Rowing Club consisted of “many of our first and best young men, full of vim and ambition, and determined to make for themselves a reputation in the rowing arena.” However, as always with time, things change, and due to low membership fees, rowing trickled into all social classes and would soon become a sport for all people (Somers 152).

Before the war, rowing was reserved for members of high society, and this trend continued only for a short time after the war. On August 25, 1872, New Orleans Daily Picayune boasted that the Pelican Rowing Club consisted of “many of our first and best young men, full of vim and ambition, and determined to make for themselves a reputation in the rowing arena.” And again, on May 7, 1875, the Daily Picayune spoke of the St. John Rowing Club as “‘a club of high social standing—perhaps the highest occupied by any club in New Orleans. Its members are chiefly young gentleman of polish and attainments and fashionable proclivities whose associations are with the first people of the city.’” However, as always with time, things change, and due to low membership fees, rowing trickled into all social classes and would soon become a sport for all people (Somers 152).

The shared love of athletic pursuit and competitive rivalry crossed socio-economic boundaries and brought equality to the rowing community. Employees of New Orleans cotton presses started the Orleans Rowing Club in 1873, and workers in metal foundries started the Riverside Club that same year. In the 1870’s, always looking for a good workout, fireman created several associations, including two very successful rowing clubs, Hope and Perseverance. Frank J. Mumford, a fireman, cotton weigher, and a oarsman for the Perseverance Rowing Club, was one of New Orleans’s best rowers in the 1870’s and 80’s (Somers 153).

On July 16, 1874, the Times Picayune announced the Riverside Crew’s record setting time at the Pelican Club’s Annual Regatta on Bayou St. John. The Orleans, Pelican, and Riverside Clubs brought a crowd that “was far greater than on any previous occasion. ” The Riverside team beat the Pelicans in what was called “the best time ever made on the bayou.” Of course, in true New Orleans style, both winners and losers ended the evening dancing together.

On July 16, 1874, the Times Picayune announced the Riverside Crew’s record setting time at the Pelican Club’s Annual Regatta on Bayou St. John. The Orleans, Pelican, and Riverside Clubs brought a crowd that “was far greater than on any previous occasion. The houses of the St. John and Pelican Clubs were covered with their guests; the two bridges held over a thousand, whilst the rows that covered both sides of the bayou must have swelled the total to at least five thousand.” The Orleans and Pelicans competed first, with the Pelicans taking the win. Then, the Pelicans and the Riverside crews raced, and the Riverside crew won. That outcome determined the final battle: Pelicans versus Riversides. After a short break so athletes could rest and spectators could place their bets, the two teams raced for the title on a two mile course. The Riverside team beat the Pelicans in what was called “the best time ever made on the bayou.” Of course, in true New Orleans style, both winners and losers ended the evening dancing together.

On June 16, 1878, the Times Picayune reported that the anticipation for the Southern Yacht Club of New Orleans’ inaugural regatta was palpable. Old contenders repaired large portions of their boats and new contenders caused even more anxiety because their boats’ performance was unknown. To entice more spectators, the member of Southern Yacht Club threw a party (or “hop”) at the St. John Rowing Club boathouse after the races. Guests were able to watch and bet on the regatta from the boathouse and waste no time getting to the hop.

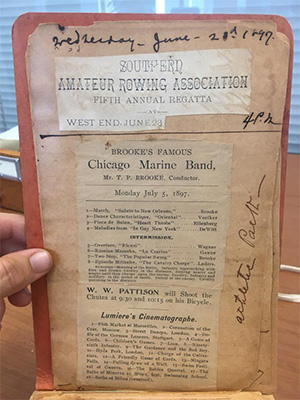

Before 1893, the New Orleans vicinity amateur rowing clubs had united together as the Pontchartrain Rowing Association. But, in the spring of 1893, the association dissolved. The St. John Rowing Club and the Louisiana Boat Club, two former members of the Pontchartrain Rowing Association, formed The Southern Amateur Rowing Association and began extending invitations. Soon, the Southern Amateur Rowing Association included one club from Pensacola, the Southern Racing Club, and five from New Orleans: the St. John Rowing Club, Louisiana Boat Club, West End Rowing Club, Tulane Rowing Club, and Young Men’s Gymnastic Rowing Club. After 1893, all Southern Amateur Rowing Association races were held on Lake Pontchartrain except the race of 1898, which took place in Pensacola. Each race attracted such a crowd and rewarded such a prize that the competition was fierce and records were set.

Dating back to its founding on August 29, 1879, the Louisiana Boat Club was considered one of the oldest rowing clubs in New Orleans. In 1894, the Louisiana Boat Club won thirteen out of sixteen medals offered at the championship regatta. In 1880, the Orleans Rowing Club, started in 1873 by men who worked the cotton press, shuttered its boathouse; however, many of its old members formed the West End Rowing Club. The West End Rowing Club boasted some of the finest oarsmen and won championships in 1896, 1897, 1898. At a regatta in Pensacola in 1898, the Crescent Rowing Club morphed into a new club called the Young Men’s Gymnastic Club’s Rowing Club (Y.M.G.C), now known as the New Orleans Athletic Club. They won the championship in 1899.

Dating back to its founding on August 29, 1879, the Louisiana Boat Club was considered one of the oldest rowing clubs in New Orleans. After incorporating under charter in 1883, the Louisiana Boat Club made a name for itself. In 1894, the Louisiana Boat Club won thirteen out of sixteen medals offered at the championship regatta. In 1880, the Orleans Rowing Club, started in 1873 by men who worked the cotton press, shuttered its boathouse; however, many of its old members formed the West End Rowing Club, fully incorporated in May 1890. The West End Rowing Club boasted some of the finest oarsmen and won championships in 1896, 1897, 1898. At a regatta in Pensacola in 1898, the Crescent Rowing Club morphed into a new club called the Young Men’s Gymnastic Club’s Rowing Club (Y.M.G.C), an extension of the Young Men’s Gymnastic Club (Now known as the New Orleans Athletic Club). They had a two-story clubhouse on Bayou St. John and won the championship in 1899.

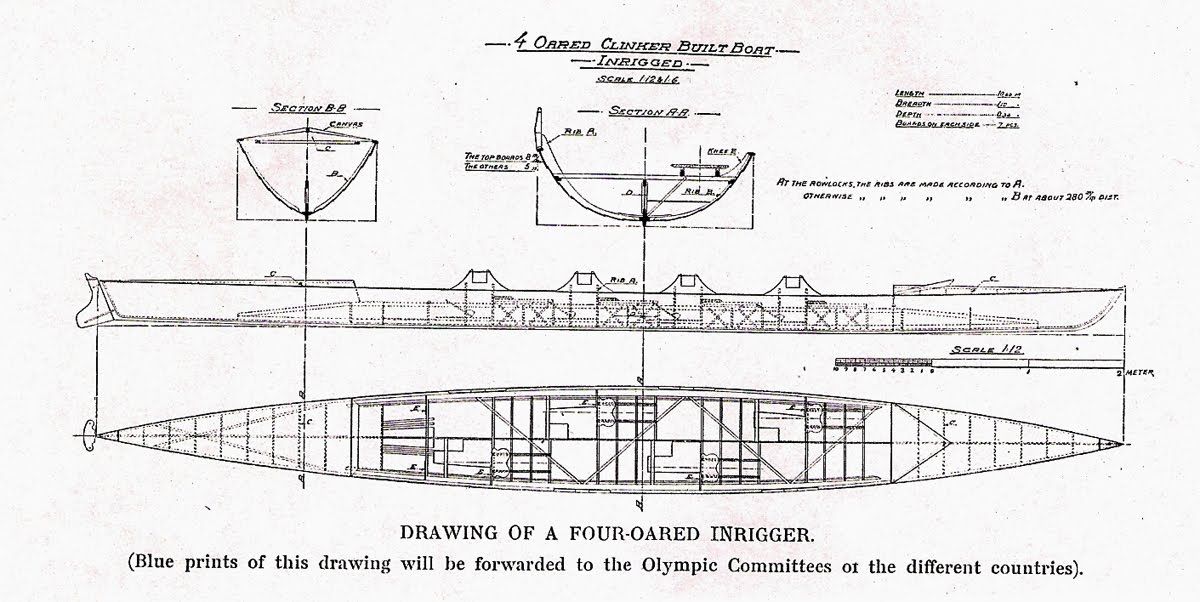

On June 19, 1879, the Times Picayune covered the second day of the Hope Rowing Club’s regatta between the Hope, Perseverance, Atlantic, R.E. Lee, Eclipse, and Riverside Clubs. The event consisted of three races: the double scull shell, the four-oared barge, and the four-oared shell. It was a beautiful day, with water like glass, and “an immense concourse of people at an early hour assembled […] and crowded every available place from which a view of the course could be commanded.” Hope Rowing Club won the double scull shell, the four-oared barge, and the most popular race, the four-oared regatta – a sweep of gold medals for the home team!

Competitions between clubs grew intense during interclub matches, anniversary races, and state championships. When transport options increased, Louisiana athletes traveled to regattas in the Midwest and Northeast, and, in turn, out-of-state athletes would flock south for the chance to row the waters of the Big Easy. The St. John Rowing Club hosted extravagant regattas in 1875, 1880, and 1885, luring top oarsmen from places like New York, Chicago, Detroit, Charleston, Galveston, Mobile, Michigan, and Iowa. These races garnered much attention in newspapers, including The New York Times, and sports journals across the country. But, the 1885 race proved to be a financial nightmare, and so the St. John Rowing Club returned to only hosting local competitions (Somers 153).

On June 4, 1880, the ever-prominent New York Times reported on the St. John Rowing Club’s first day of its 1880 interstate regatta the previous day on Lake Pontchartrain: “The weather was clear and warm, the attendance large, and the water smooth.” Participants from many rowing clubs competed, including St. John, Orleans, Louisiana, Pelicans, Cohoes (NY), Neptunes, Hillsdales (MI), Riversides, and Pensacolas (FL). The course was a simple, straight, one and half mile stretch with four events: junior single scull, four-oared wherry (a light rowboat), the double scull, and the four-oared barge. Hillsdale won the double scull; Gus Soniat, from the St. John club, won the junior single scull. The St. John club also won the four-oared wherry, but the Neptunes would beat the Pelicans in the four-oared barge.

For a country still licking the self-inflicted wounds of the Civil War, intersectional regattas were seen as a way to bring the country back together on common ground. Fans cheered equally for Southern and Northern teams and bonded over the excitement of competition. This was not a time to reignite old battles, but a time to heal through the joy of athletic pursuit. In fact, at the St. John regatta in 1880, Congressman R.N. Ogden announced: “these are the contests we desire, contests of manly skill, and prowess, embittered by no sectional prejudice, inflamed by no political animosity, contests of brotherly love, where the best man wins” (Somers 154).

Many local rowers competed at out-of-state regattas in the North. The Hope, Perseverance, St. John, and West End rowing clubs all sent athletes to city, regional, and national events. In 1877, the very first New Orleans oarsmen to race outside the city, James O’Donnell, earned 2nd place at a single-scull race in Detroit. When O’Donnell made it back home, his club welcomed him in true New Orleans fashion – with a band and a second line through town (Somers 153-154).

The pride of the Perseverance Rowing Club, Frank J. Mumford was, without a doubt, the best competitor at out-of-state events. In both 1879 and 1880, Mumford crushed the competition in the single-scull championships held by the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen. He twice won the same event held by the Mississippi Valley Rowing Association. The Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times referred to Mumford as “the finest oarsmen who has ever pulled in the Association.” C.S. Titus, a student of Mumford’s, would continue his coach’s legacy by dominating the single-scull championships in 1901, 1902, and 1906 (Somers 154).

Although the competitions between other states were intense, the spectators loved the state championships the best. Because fans demanded entertainment, because more clubs appeared each year, and because athletes truly desired non-political, positive, “best man wins” rivalries, governing bodies were needed to pay for and regulate the action. Four separate groups were formed: Louisiana Rowing Association (1873-1874), Louisiana Amateur Rowing Association (1875-1884), Pontchartrain Regatta Association (1881-1893), and Southern Amateur Rowing Association (1898-1900). Thanks to these organizations and their sponsorship, local oarsmen were able to compete in regattas yearly from 1873-1900. But, a club from Pensacola, FL shook things up they joined the Southern Amateur Rowing Association in 1894. Annual races were held in New Orleans or Pensacola from that point on, and athletes competed in the “southern championship” (Somers 155).

The biggest concern of the rowing community was keeping the athlete and the competition pure. The four rowing associations abided by the rules set by the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen (NAAO) and therefore quelled any “professionalism” issues. The St. John club, however, went rogue and joined the Mississippi Valley Rowing Association instead, but they accepted NAAO authority as well, so it didn’t really matter. Somehow, Frank Mumford, “the finest oarsmen” got banned from competition for supposedly, as reported by the New Orleans Daily Picayune on August 12, 1884, “rowing crooked” (Somers 155).

The biggest concern of the rowing community was keeping the athlete and the competition pure. The four rowing associations abided by the rules set by the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen (NAAO) and therefore quelled any “professionalism” issues. The St. John club, however, went rogue and joined the Mississippi Valley Rowing Association instead, but they accepted NAAO authority as well, so it didn’t really matter. The NAAO ruled that an amateur athlete was “any person who has never competed in any open competition for money, or under a false name, or with a professional for any prize, or where gate money is charged, nor has ever, at any time, taught, pursued, or assisted in athletic exercises for money or for any valuable consideration.” The NAAO and rowing associations were so successful at their mission that only once, in 1884, did anyone ever break the code. Somehow, Frank Mumford, “the finest oarsmen” got banned from competition for supposedly, as reported by the New Orleans Daily Picayune on August 12, 1884, “rowing crooked” (Somers 155).

On August 12, 1884, New Orleans Daily Picayune confirmed that Frank Mumford, who was known as the city’s best rower, had been disqualified by the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen (NAAO) “for rowing crooked.” And this wasn’t the first time Mumford’s integrity was questioned. In 1880, the NAAO arranged for a committee to investigate his supposed “hippodroming of races in the interest of poolroom gangs.” He was suspended for this, but later pardoned in 1881. The “rowing crooked” suspension lasted four years, until the NAAO reconsidered the case in 1898. Mumford returned to rowing, but his time was short-lived. In 1900, he succumbed to pneumonia while training for a race and died (Somers 156).

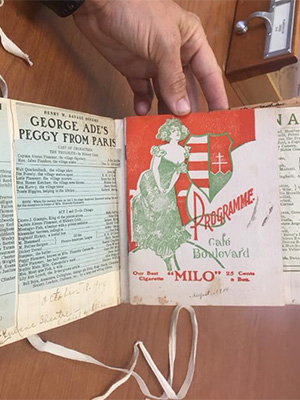

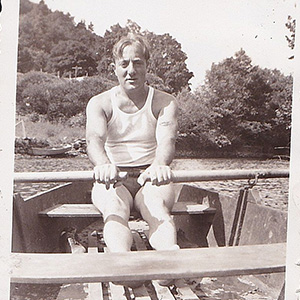

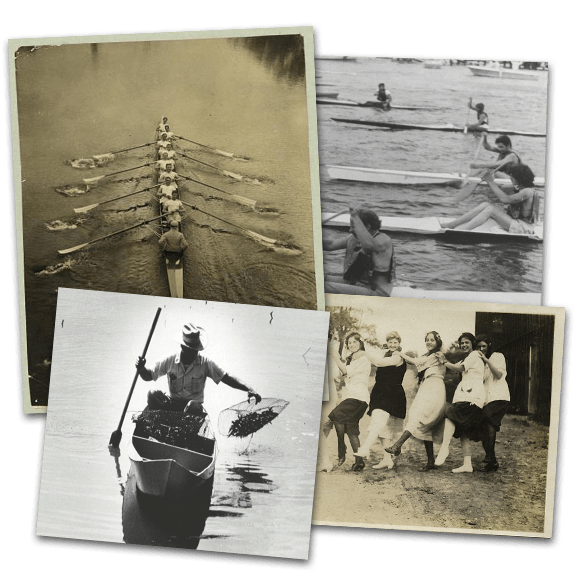

Due to the dedication of the athletes and the guaranteed purity of the sport, rowing became one of the most popular sports of the 1870’s and 1880’s. Crowds of over 15,000 packed the banks during regattas and oarsmen enjoyed celebrity status. The press would hound visiting rowers from the second they set foot at the station or harbor and drill them about their regimens, records, and dreams. And the ladies! Oh, the ladies. On June 21, 1885, The New Orleans Daily Picayune reported that “a great many ladies graced the clubhouse balcony, and the oarsmen had the additional encouragement of a band of music.” Eager to impress, the rowers flexed extra hard to the beat as they pulled passed. It was a great time to be oarsmen (Somers 156).

Rowing was so popular and oarsmen were so revered by women that rowing terminology entered the dating world. The New Orleans Bulletin reported, on August 15, 1875, that “young women no longer ask for an arm; it is, ‘Give me your starboard oar, please.’" Many women desired to hold the arm of an oarsman – and this lasted for quite some time. A June 4, 1880 New Orleans Daily Picayune article claimed that women were weak for rowers: “Women, who are by nature weak, delight to gaze upon the evidences of strength in the other sex. The brawny arm and sinewy frame, which the oarsmen develop to the utmost, are objects of the deepest admiration to them.” (Somers 156).

Rowing was so popular and oarsmen were so revered by women that rowing terminology entered the dating world. The New Orleans Bulletin reported, on August 15, 1875, that “young women no longer ask for an arm; it is, ‘Give me your starboard oar, please.’ …In the evening, not a waltz, but a ‘double-scull race’ is suggested.” Many women desired to hold the arm of an oarsman – and this lasted for quite some time. A June 4, 1880 New Orleans Daily Picayune article claimed that women were weak for rowers: “Women, who are by nature weak, delight to gaze upon the evidences of strength in the other sex. The brawny arm and sinewy frame, which the oarsmen develop to the utmost, are objects of the deepest admiration to them. The victor in the athletic struggle finds his sweetest reward in the bright glance and smiles of approval from their eyes and lips.” When a fine woman is a winner’s prize, a man finds himself with no other want or need of motivation (Somers 156).

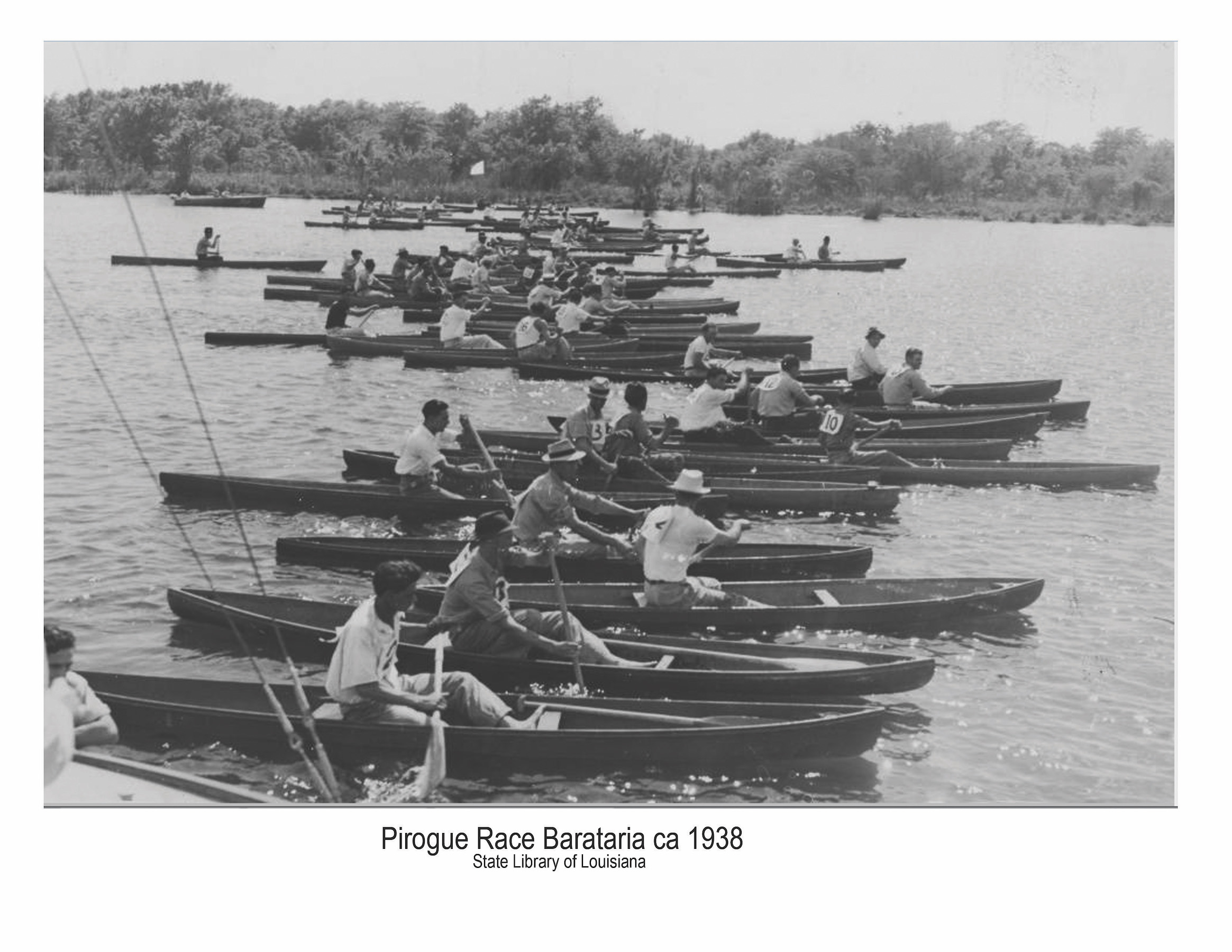

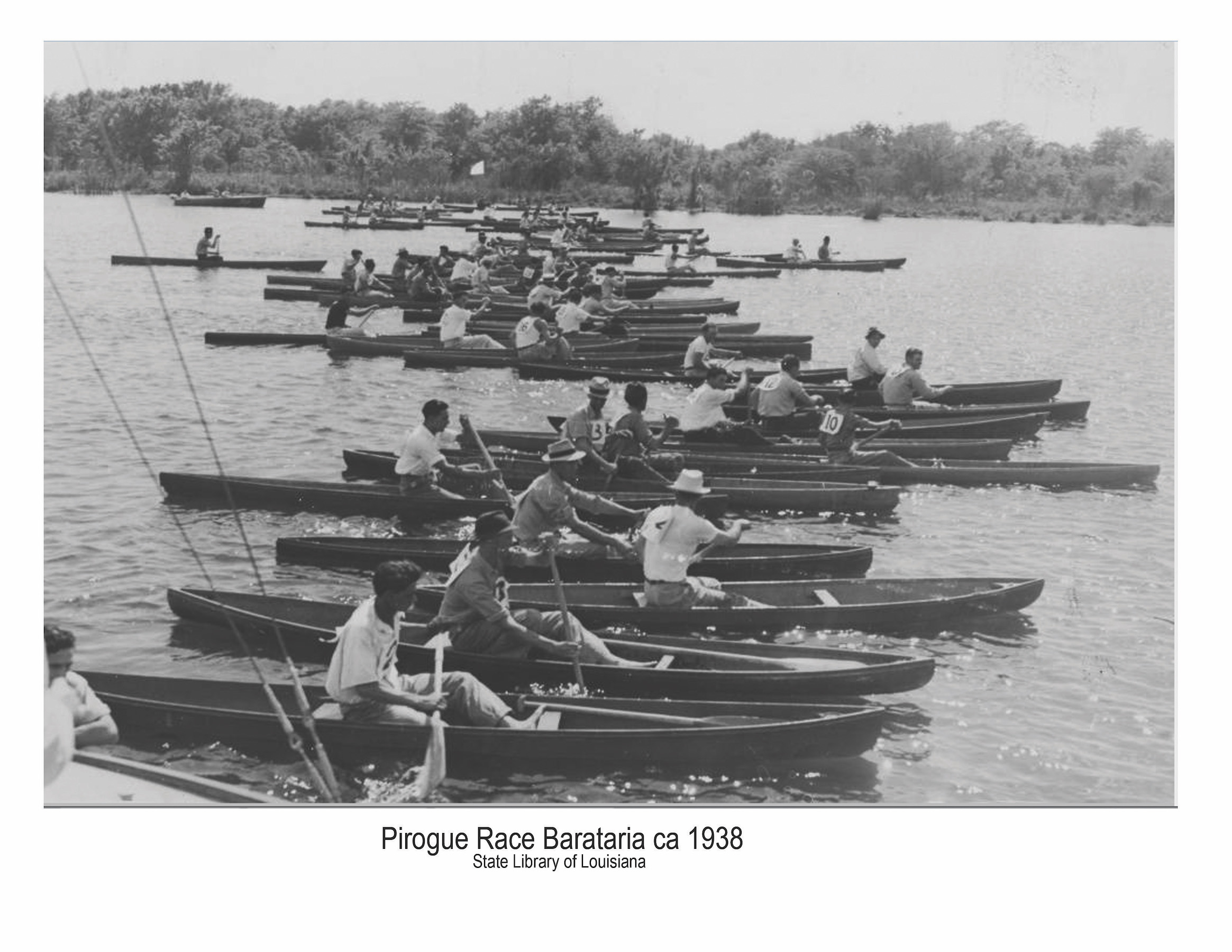

In the 1883 article, “Pleasant Evening with the Louisiana Boat Club,” the Times Picayune proved that the Louisiana Boat Club’s reputation for throwing a grand day at the races was true. They provided good music, great hospitality, wonderful scenery, and exhilarating competition. Spectators were treated to a “pluckily contested” pirogue race and a tub race that “afforded no end of amusement.”

In the 1883 article, “Pleasant Evening with the Louisiana Boat Club,” the Times Picayune proved that the Louisiana Boat Club’s reputation for throwing a grand day at the races was true. They provided good music, great hospitality, wonderful scenery, and exhilarating competition. Spectators were treated to a “pluckily contested” pirogue race and a tub race that “afforded no end of amusement.” During the tub race, “contestants who fought for glory in the treacherous tubs which slipped from under when they seemed most willing to behave” would be “followed to the other side by the laughter of the ladies.” That had to be the hardest part for the athletes. The racing concluded with a barge race, and the victors were especially proud because “each oarsman had his chosen lady beside him, and it was to win her a beautiful souvenir in the shape of a monogram pin that he put forth his best efforts.” And then there was dancing. That night, the Louisianas proved themselves on the dance floor and on the water, “bringing smiles and blushes to the faces of the fair partners.”

As other sports like baseball gained more popularity in the 1890’s, many rowing fans grew distracted and rowers from the lower and middle class grew disinterested. A few storms also caused devastating damage. Rowing once again fell under the jurisdiction of “athletes from the upper levels of society who showed little desire to revive popular enthusiasm for the sport.” These athletes wanted the sport socially exclusive and were most concerned with “preserving the sport as a pastime for gentleman.” The West End and St. John Clubs limited their activity to state championships and an annual anniversary regatta, and only close friends and relatives were invited to in the clubhouses. The St. John Club let their huge grandstand, capable of seating 5,000, slowly rot on the bank (Somers 157).

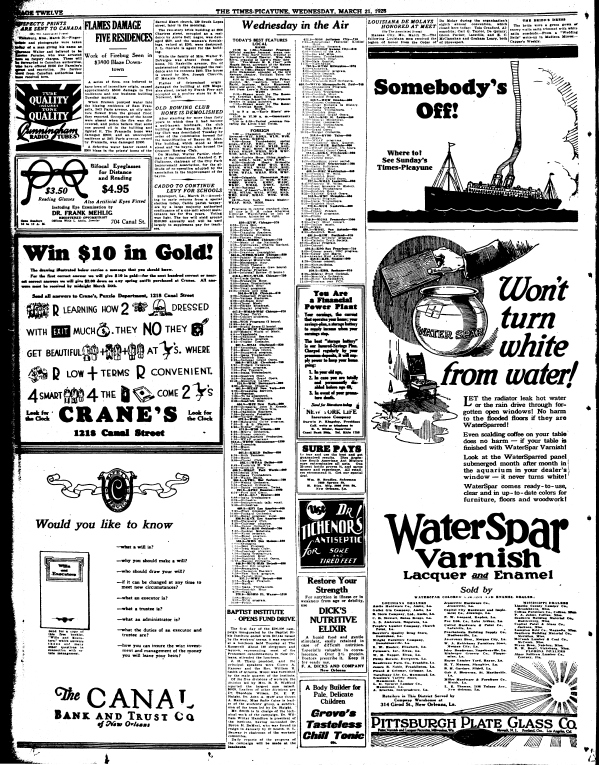

The St. John Rowing Club built its clubhouse in 1885, including a bar, poolroom, and a grandstand that could hold 5,000 people in preparation for its yearly extravaganza. However, the club abandoned the grandstand following a financially disastrous 1885 regatta. Rot had deteriorated the structure by 1900 (Somers 157). On March 21, 1928, The Times Picayune reported that the last of the beloved Bayou St. John Rowing Club clubhouse had been demolished by the Bayou St. John beautification commission. A “well-known landmark” gracing the shores for forty years, the building was also home to the Crescent Rowing Club.

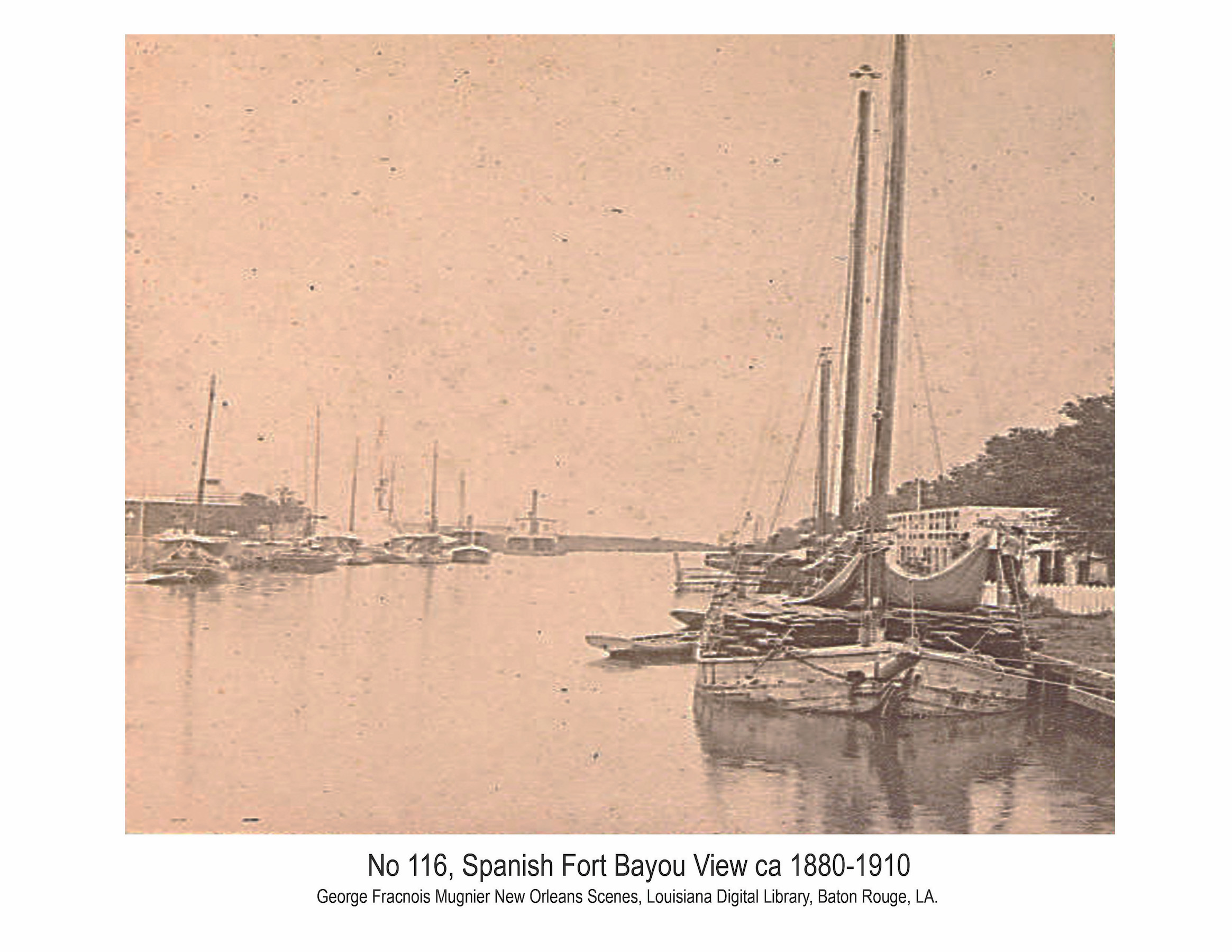

By 1900, boat clubs had mostly disappeared and even the high society youth lost interest. In 1909, the railroad purchased the West End area by Spanish Fort, abandoned and disintegrating after the Civil War, and turned it into a park. The railroad wanted to build an amusement park, but compromised with a green park and a Spanish Fork line extension of their West End line. In 1915, a fountain appeared, and, by 1922, two restaurants moved in. The Municipal Yacht Harbor, built by the WPA between 1938 and 1940, sat on the lakeside of the West End Park, and Orleans Marina appeared, courtesy of the Orleans Levee Board, along the inner harbor in 1962. People are drawn to water, and people like to have fun on and in water. And so our liquid traditions resurfaced as apartments were built in the area in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Water enthusiasts and their supportive spectators slowly gathered in the city again. (Stuart).

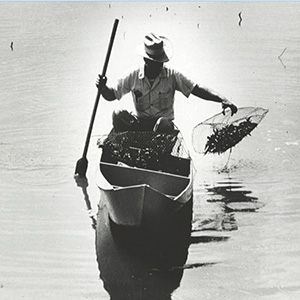

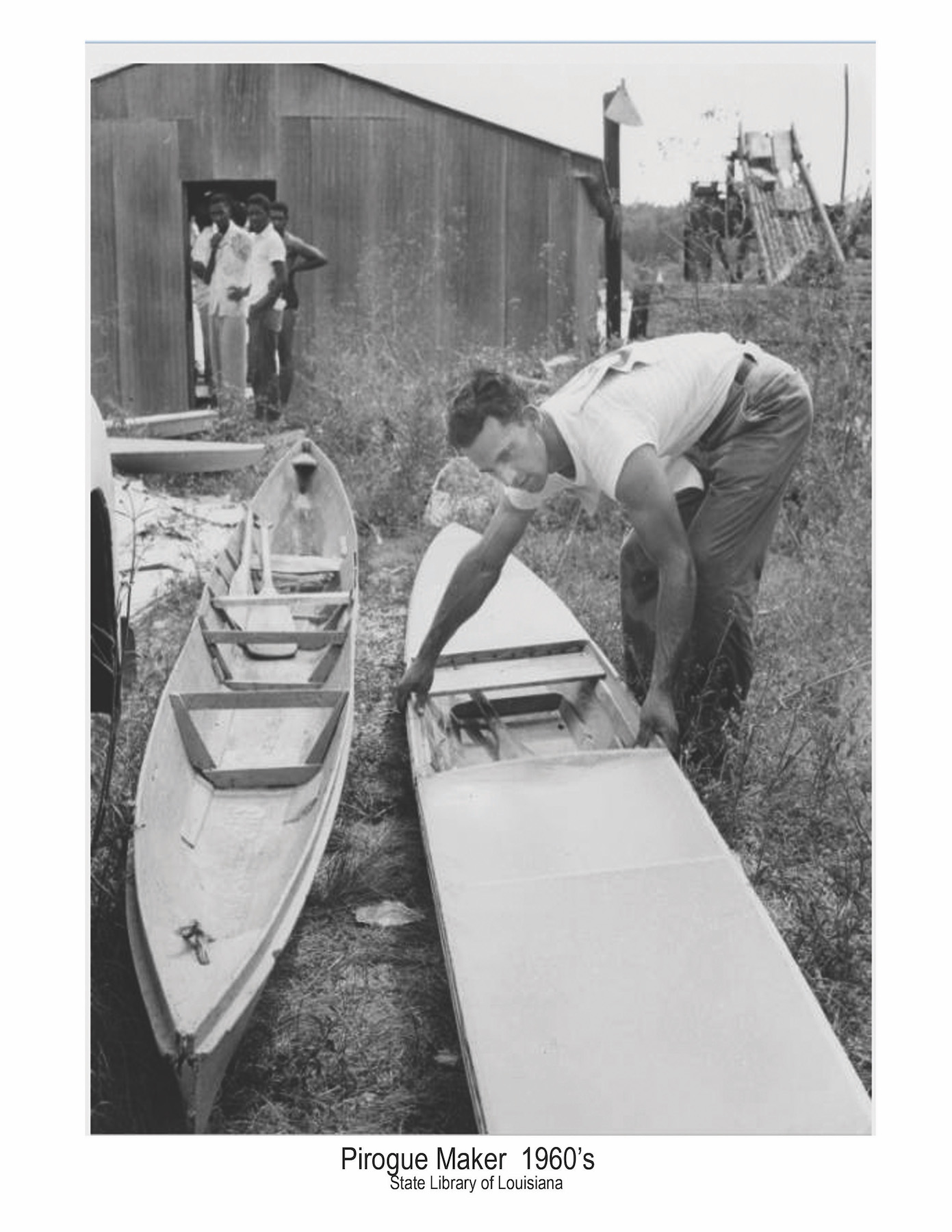

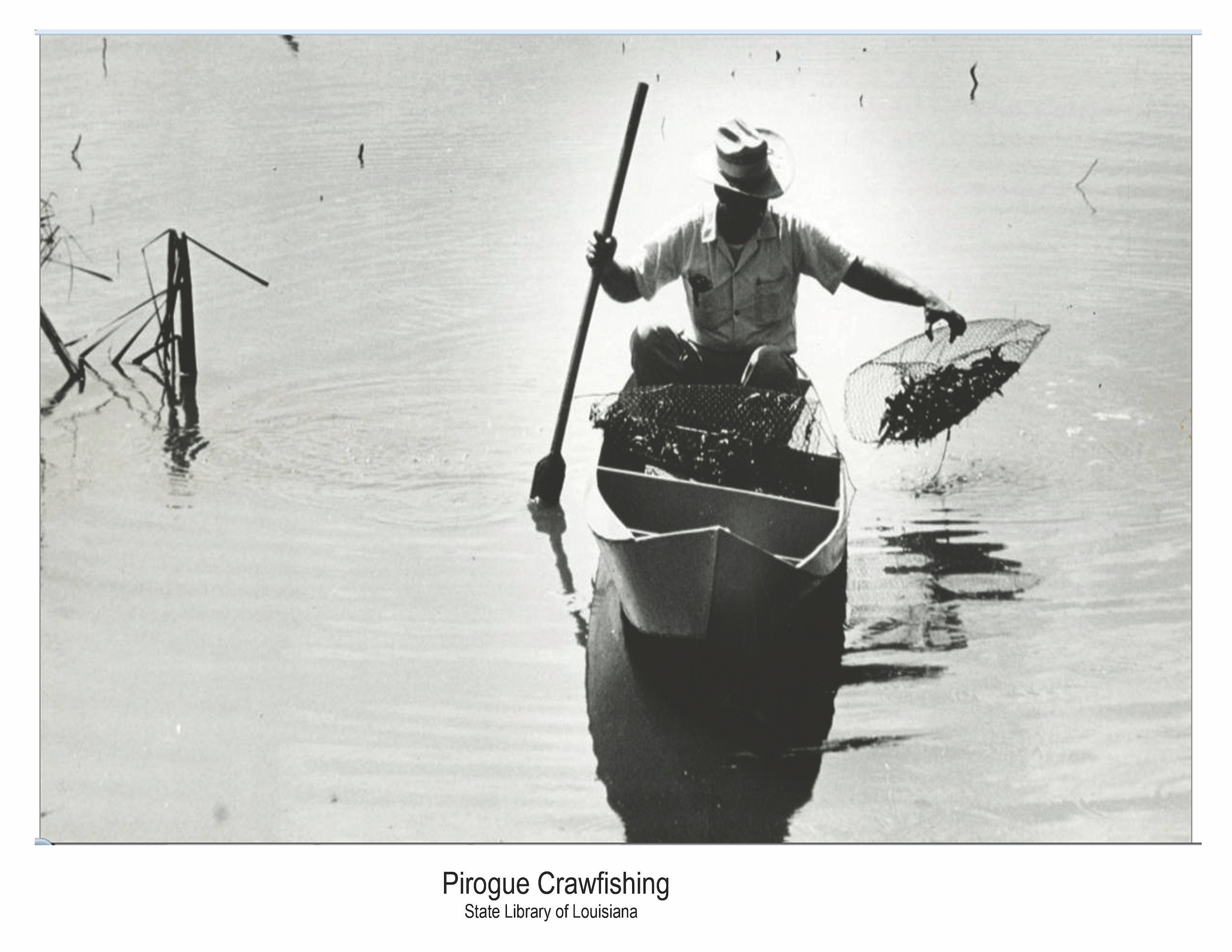

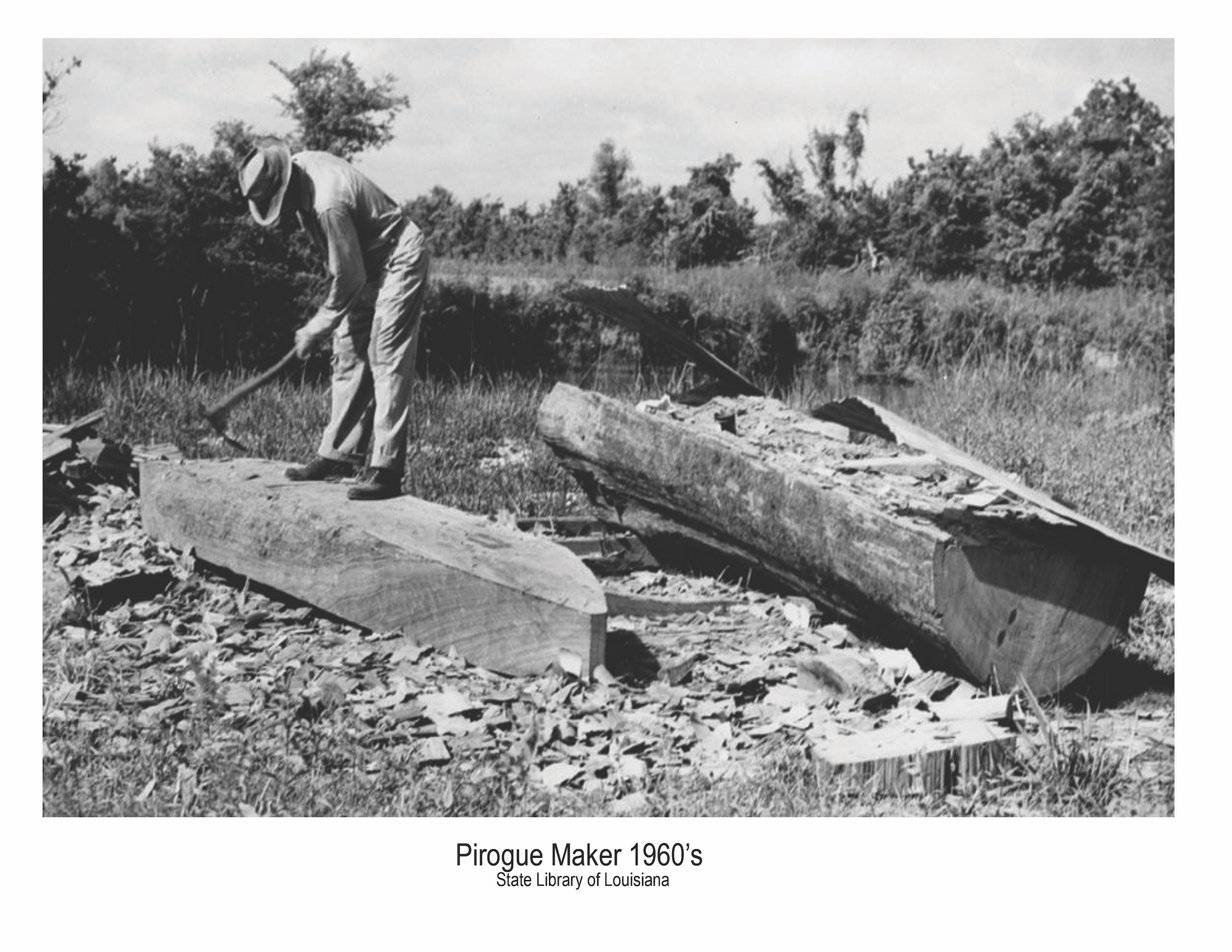

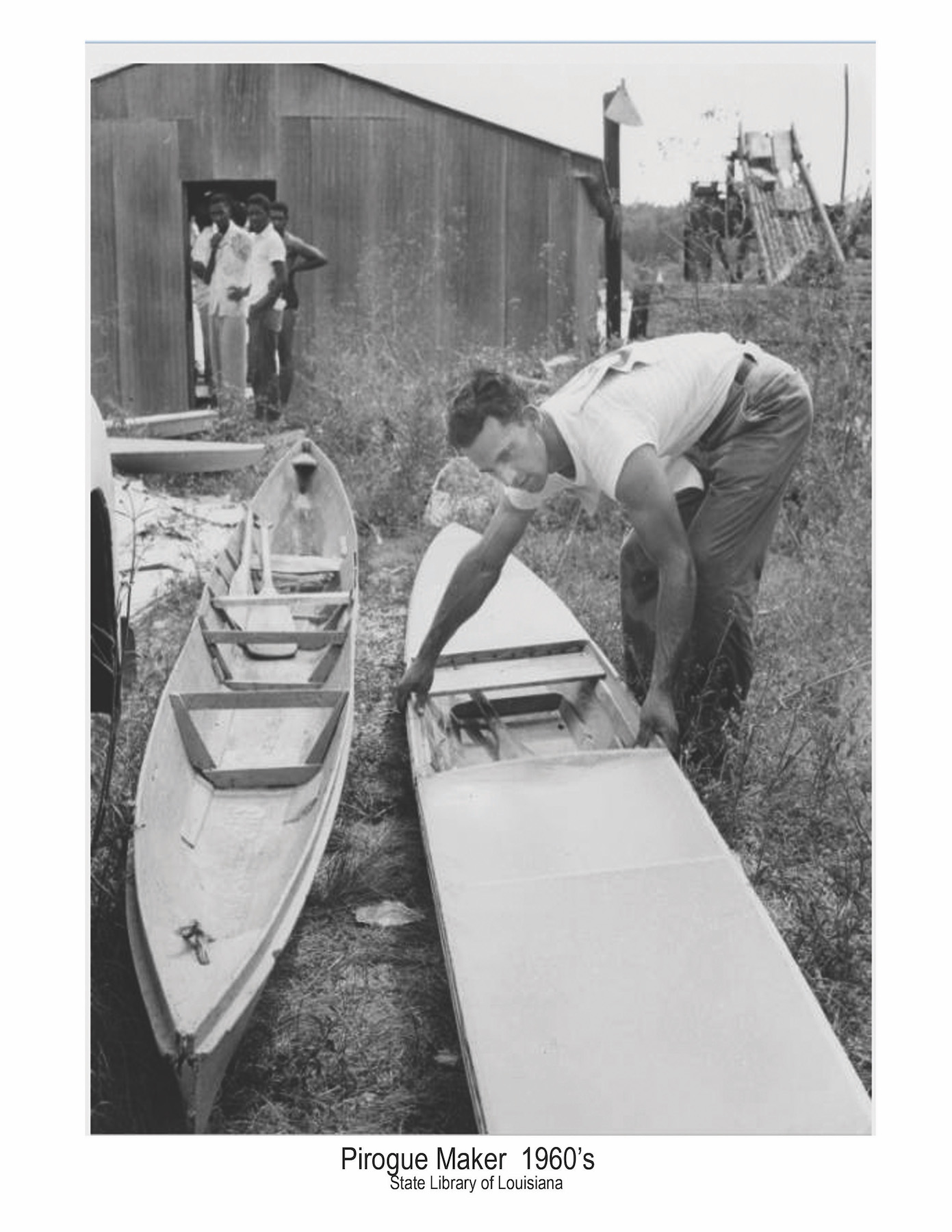

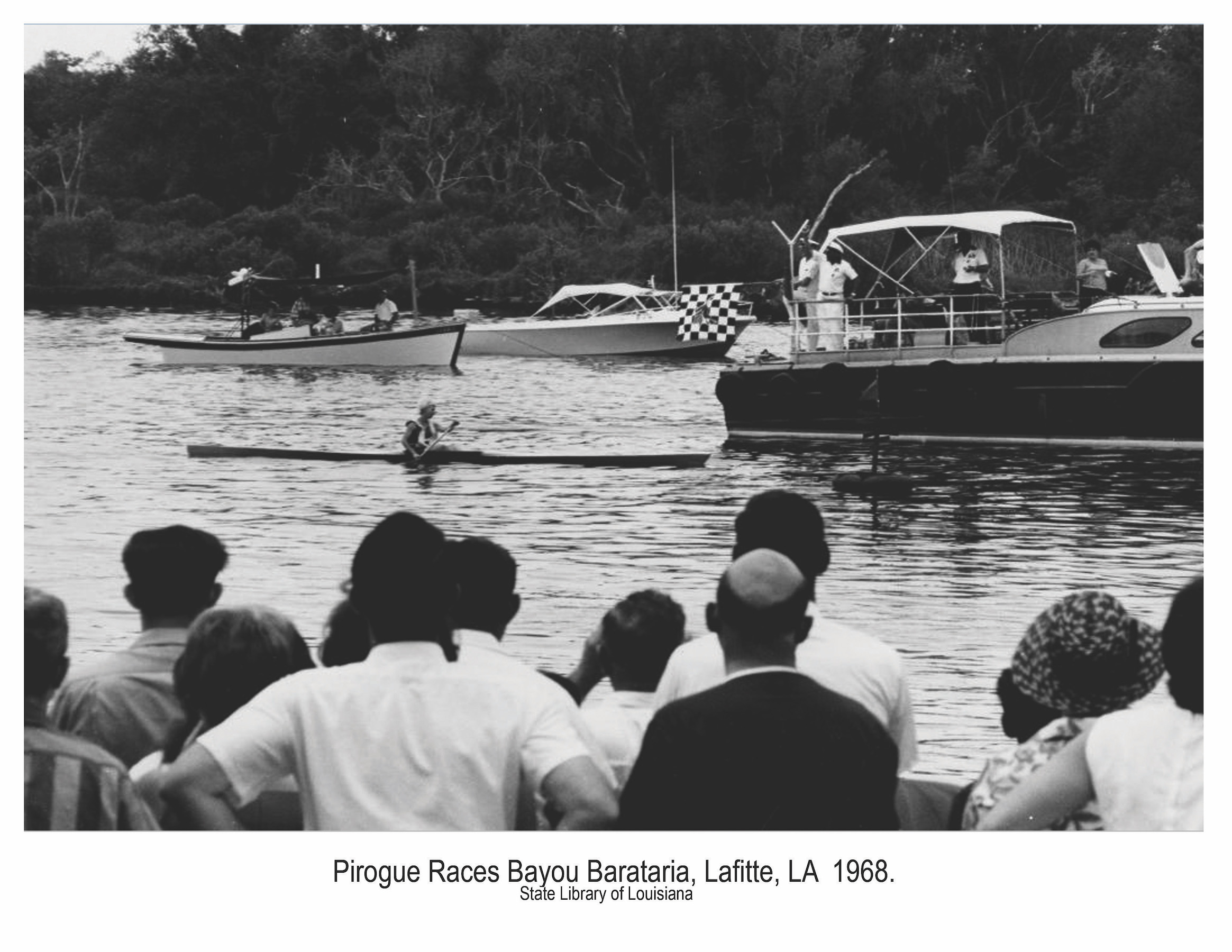

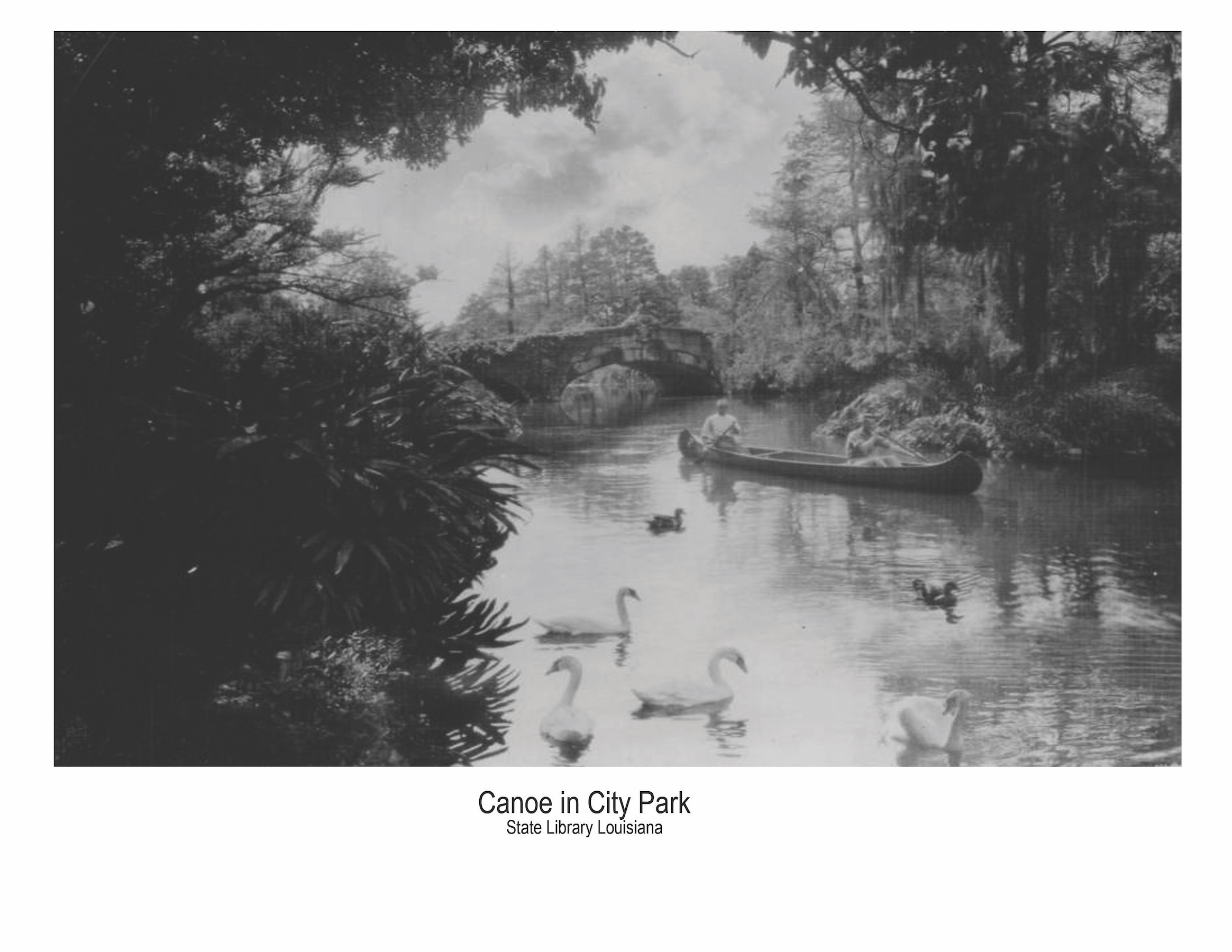

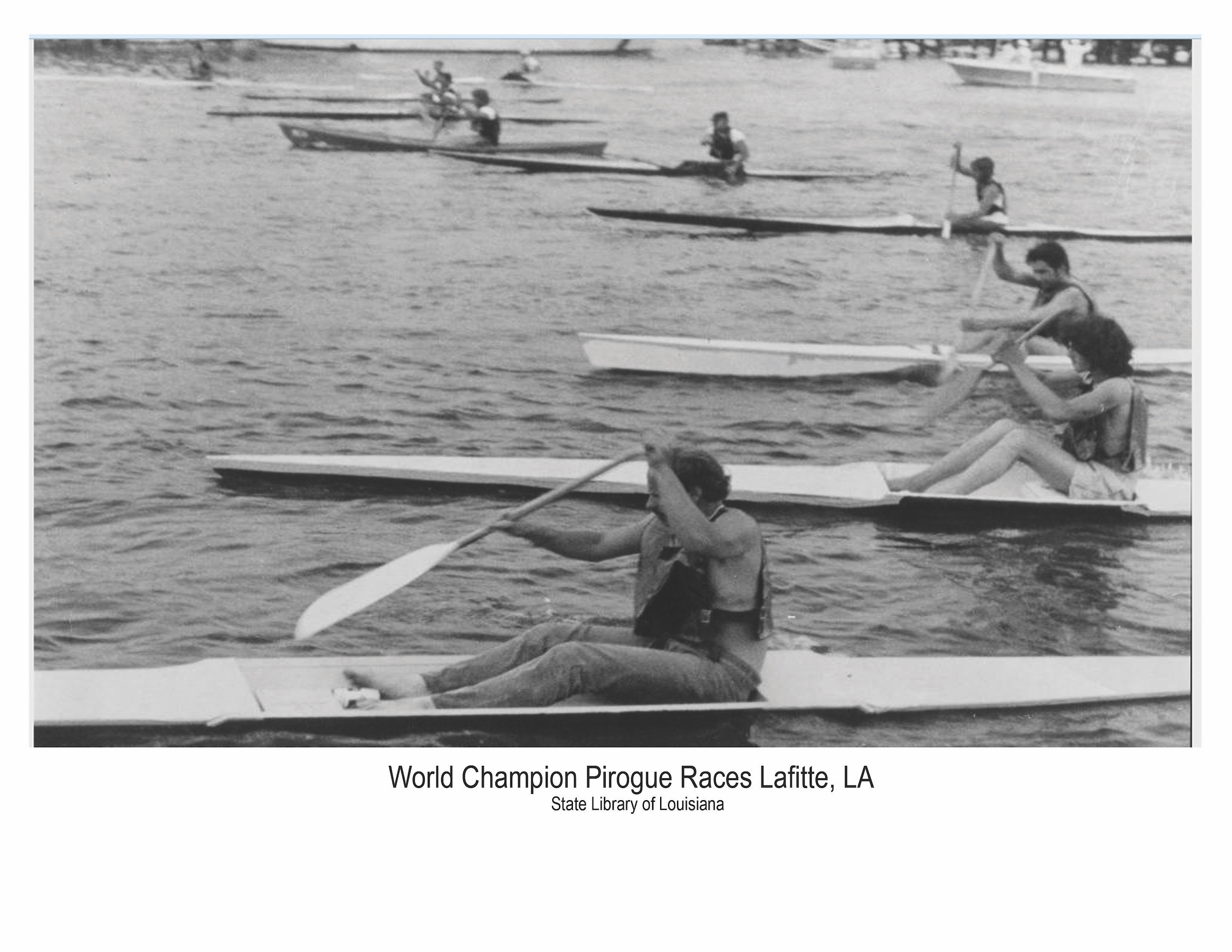

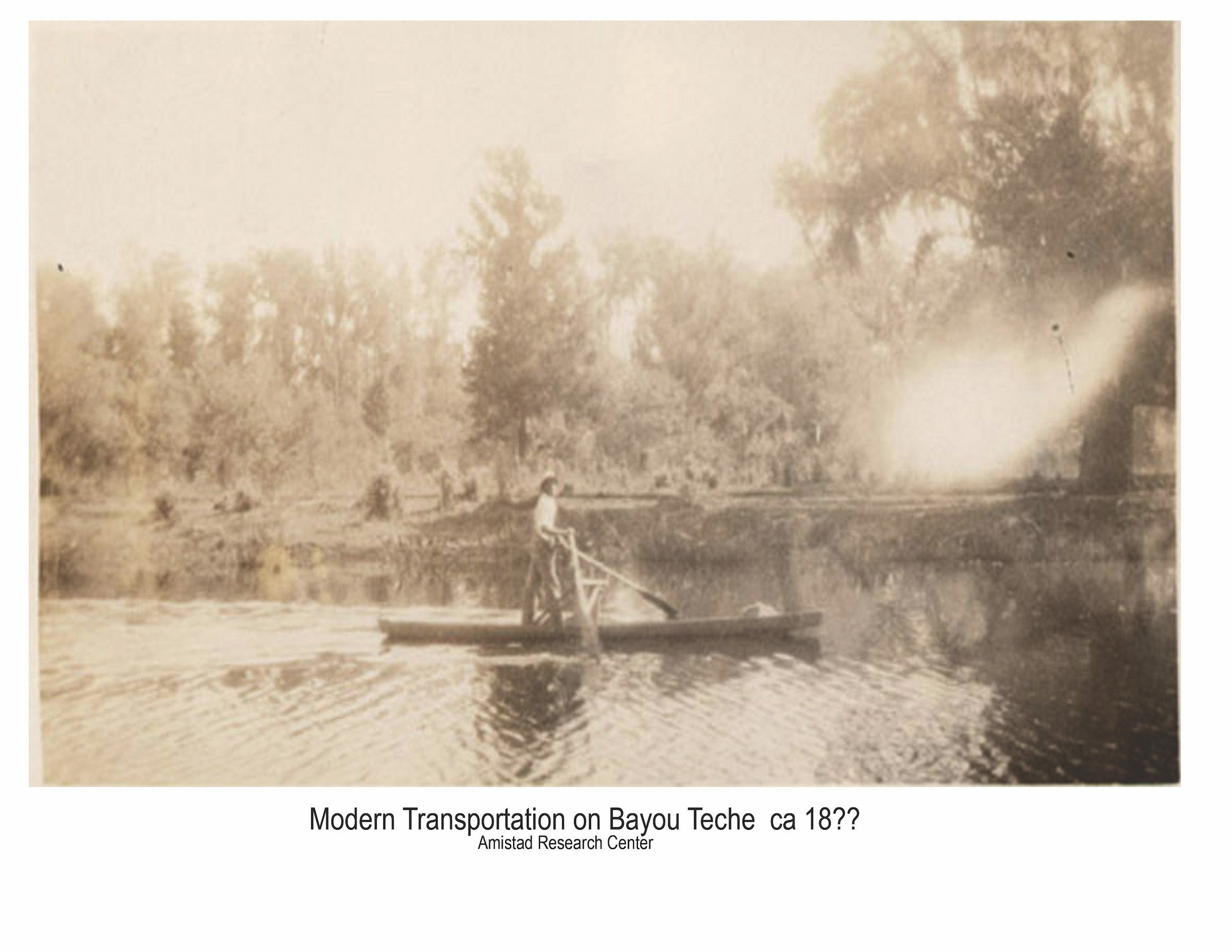

From the 1900’s to the Great Depression, paddling continued on a smaller scale. Some rowing clubs remained in the city and held regattas, and people who lived on or near the bayous used pirogues (small boats that resemble kayaks and canoes) as a way of life. In the same day, one might have used his pirogue to catch crawfish to eat or sell, and in the evening, that pirogue was also battling in a race on Bayou Barataria. A paddling life was present, just in a different way.

In a 1915 article titled “St. John Rowing Club Eight Again Defeats Pontchartrain,” the Times Picayune covered the final race of the 1915 amateur rowing season between the St. John and Pontchartrain Rowing Clubs. This was the fourth time that the two teams faced each other, but Pontchartrain’s 1912 record still stood. Fans expected a battle in which records would be broken, and so spectators lined the two mile course. St. John won the race by a considerable amount, but both teams “forgot their difficulties of the afternoon and made merry of a banquet at Spanish Fort.”

On October 13, 1934, people journeyed from far and wide, from nearby parishes and bayou country, to witness the pirogue race held by Barataria Women’s Club. The race was just about five miles, and the Commodore for the races decided the post positions with a card trick. Maturin Billot, a 39-year old grandfather, won the race in a borrowed pirogue. To Maturin, the prize was neither the silver nor the $18; the true prize was winning respect for the bayou country from everyone.

If a club or boat survived the Great Depression, and then the series of storms that hit the area, it was lucky to be around. Bayou dwellers still made and used pirogues as a way of life, and pirogue races and tipping contests were commonplace.

On May 21, 1975, The Times Picayune announced that New Orleans would hold its first annual France-Louisiana Festival from July 4 – 14, 1975. The festival purposely stretched over ten days in order to connect July 4, American Independence Day, with July 14, French Bastille Day. To celebrate both countries’ national independence, the festival boasted visual and performance arts, street entertainment, crafts, puppet shows, and music. On July 12, the popular Bastille Day activities kicked off, opening with French bowling, fireworks, pirogue races on Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain, and a regatta.

On Sunday, July 19, 1936, right under a picture of the new Wimbledon Champion in action, the Times Picayune announced that New Orleans would return to the rowing scene on July 21, 1936 in the New Basin Canal. It was the first regatta since 1929, when the Pontchartrain Rowing Club at West End, and all its equipment, burned to the ground. The race included four events: a novice and a junior wherry, senior doubles, and senior four-oared shells. In order to win, competitors had to row the ½ mile course in the fastest time. This race was the first of three summer events planned by the Pontchartrain Rowing Club in 1936.

In 2011, Bayou Kayaks was born along the banks of Bayou St. John in hope of sparking a paddling revival in New Orleans. Tourists and locals alike flocked to the Moss Street launch site to explore the city, and its wildlife, from a different perspective. Bayou Kayaks changed its name to Bayou Paddlesports in 2014 or 2015. This “little outfitter with a big outfitter attitude” is now an integral part of the New Orleans Community, organizing and/or participating in bayou clean-ups, school field trips, sports training, weddings, birthday parties, and festivals.

In 2011, Bayou Kayaks was born along the banks of Bayou St. John in hope of sparking a paddling revival in New Orleans. And it worked! Tourists and locals alike flocked to the Moss Street launch site to explore the city, and its wildlife, from a different perspective. Participants are taught basic paddling skills, if requested or needed, and allowed to venture through the 8-mile route at their own pace. After five years of providing an excellent and easily accessible kayak service, the business recognized customer input and added more tandem kayaks, junior kayaks, and Stand-Up Paddleboards (SUPs). Due to the expanded services provided and goal of reigniting a passion for water sports, Bayou Kayaks changed its name to Bayou Paddlesports in 2014 or 2015. This “little outfitter with a big outfitter attitude” is now an integral part of the New Orleans Community, organizing and/or participating in bayou clean-ups, school field trips, sports training, weddings, birthday parties, and festivals such as Bayou Boogaloo, 4th of July, and Greek Fest.